The cart is empty!

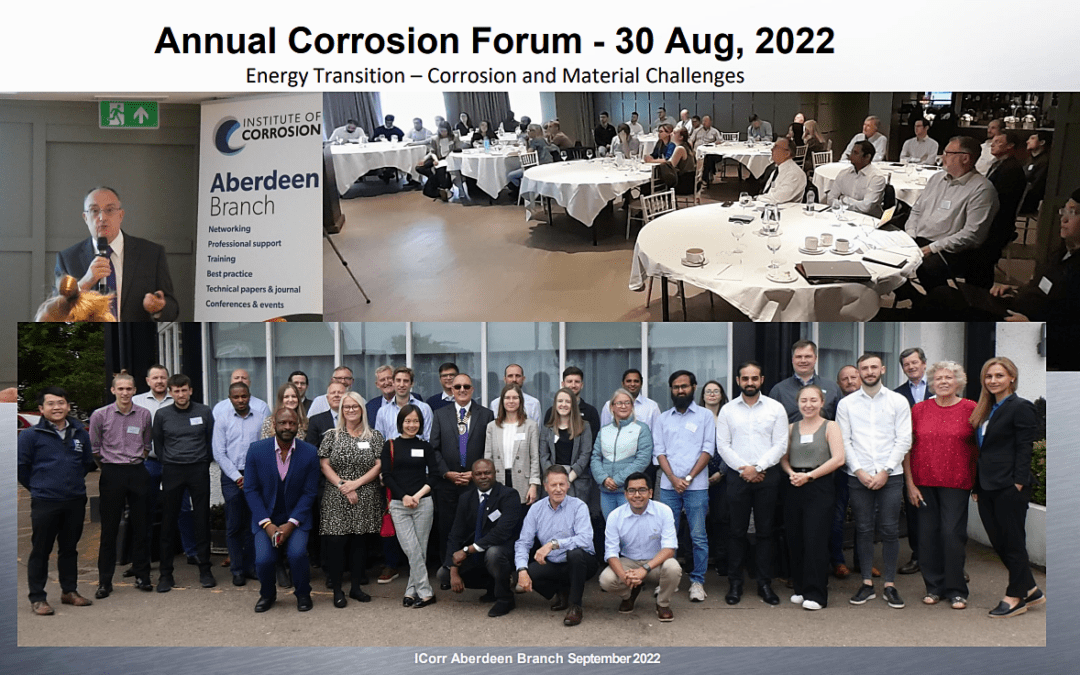

The branch held its Annual Corrosion Forum (ACF) on 30th August, on the subject of “Energy Transition – Corrosion and Material Challenges.” This was a hybrid presentation at the Palm Court Hotel, Aberdeen. There was a series of in-person and video presentations to a live audience, with a similar number of attendees registered for online viewing of the event, with 71 registered attendees in total.

The event programme consisted of a Keynote address by Dr Bill Hedges ICorr President, followed by nine talks on four topic groups, Competency and training, Pipelines, Offshore wind plus solar, nuclear and fusion energy sources, together with practical coating demonstrations run by Presserv Ltd, the key sponsor for the event.

A welcome was given by Hooman Takhtechian – ICorr Aberdeen chair, and Stuart Rennie –Manager (Presserv Ltd).

Bill Hedges then presented on the Institute of Corrosion’s approach to the energy transition landscape, which highlighted a structural materials degradation study conducted by the Henry Royce Institute in collaboration with ICorr and the Frazer-Nash Consultancy. This study looked at the degradation issues affecting structural materials and those critical to delivering the UK’s goal of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, a primary objective of which was to identify key R&D opportunities for investment by UK, viz:

• Identify issues which could slow or prevent the transition.

• Ensure the transition occurs in a safe, timely and efficient manner.

• Highlight topics that are common to several industries.

The talk focused on five industries critical for the transition,1. Wind power generation (onshore and offshore). 2. Nuclear fission (not fusion).3. Hydrogen production and usage.4. Transportation (Air, Road, Rail and Sea), and 5. Carbon Capture and storage (CCS).

Of 41 respondents from multiple sectors to the study, 123 inputs (see heat map) gave corrosion as the most dominant topic affecting infrastructure, and slowing the transition to new technologies, closely followed by fatigue.

Bill Hedges, ICorr President.

Heat Map of Royce Institute survey responses.

NPL – Carbon capture and storage.

Wood Thilsted – Offshore

wind monopile foundation.

Offshore wind coating challenges (Safinah).

ACF Dinner with Bill Hedges.

ICorr members and engineers are important to the energy transition process, and the majority of members are involved in day-to-day work in Oil &Gas, Hydrogen & Carbon Capture, Wind, Nuclear, and Battery industries.

In the subsequent competency and training session, Muhsen Elhaddad, MSc, CEng, MICorr gave a virtual presentation on the

“Roles of corrosion professionals during energy transition.”

Corrosion is still a major concern to all sectors of the economy. Losses due to corrosion are exorbitant when compared to a country’s GDP (ranges from 1 to 5% in some cases with global average of 3.4%). It is estimated that losses in fresh water supply due to damaged “corroded” infrastructure is higher than 30%. The AWWA (American Water Works Association) estimated that the cost of replacement of corroded pipe will be $325 Billion over the next 20 years. A significant part of these losses is avoidable (15 – 35%) if current knowledge is fully utilised to design, mitigate, monitor and inspect, to control or prevent corrosion.

This of course cannot happen unless there is competent and engaging corrosion and materials professionals involved at all levels of the asset cycle, from conception of the project to decommissioning. People are known to be the heart of effective asset integrity management and can make effective asset integrity happen with their proactive approach, flexibility and a quick response. They must be knowledgeable, have the right competency, and the authority to act on their knowledge, expertise and experience. They should have the means to collaborate, share and communicate at all levels of their organisation and take pride in their profession. This also requires a change in mind set and understanding that a job is not for a salary it is a profession that a corrosion professional needs to embrace and practice fully.

Muhsen’s presentation was very thought provoking and generated many questions from the audience.

For the pipeline session, Frank Cheng, University of Calgary, joined online and spoke informatively on materials constraints and safety assessment in conversion of existing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen transport.

Energy transition and realisation of new energy technologies at full scale are critical to achieving the 2050 net-zero target. Hydrogen, as a green and zero-emission fuel, has received wide attentions recently. Hydrogen delivery is integral to the entire value chain of hydrogen economy, where pipelines provide an economic and efficient means to transport. Particularly, repurposing existing natural gas pipelines is “a low-cost option for delivering large volumes of hydrogen, and similarly for CO2 transport discussed below.

There is an extensive pipeline network throughout the world, effectively transporting energy over several decades. Safety

is paramount for hydrogen transport by pipelines. Particularly, hydrogen embrittlement (HE) has been a major concern for the integrity of hydrogen pipelines. Different from “cathodic” hydrogen generated in aqueous environments where extensive investigations have been conducted, the environment potentially causing HE

of hydrogen pipelines is high-pressure hydrogen gas, in such circumstances hydrogen atom generation and permeation can occur with a mechanism totally different from the “cathodic” hydrogen.

The talk provided technical background about the HE, detailing unique features of the problem associated with high-pressure gaseous environments. Additional challenges with the conversion of existing “aged” gas pipelines for hydrogen service were discussed. These include corrosion and mechanical defects serving as hydrogen traps, pre-strain induced by pipe-soil interaction to increase the

HE susceptibility, competitive adsorption of impurity gases with hydrogen gas on steel surfaces, and preferential accumulation

of hydrogen atoms and the resulting cracking at pipeline welds. Technical gaps are being analysed, and recommendations provided for both the research community and industry to develop a technical assessment programme on the suitability of existing pipelines for hydrogen transport.

In a complimentary way and in person, Shravan Kairy – NPL continued with a discussion on the ‘Challenges in assessing corrosion resistance of pipeline steels in dense phase CO2 .”

Transportation of carbon dioxide (CO2) is essential for the storage of captured anthropogenic CO2 at dedicated locations, such as depleted oilfields. The whole process of capturing, transporting, and storing CO2 is referred to as carbon capture and storage

(CCS). CCS technology has the potential to decarbonise industrial sectors by capturing CO2 prior to its release into the atmosphere. The successful implementation of CCS technology would enable the continued use of available fossil fuels for the world’s energy needs. Pipeline transport of dense phase CO2, i.e., in the liquid

or supercritical phase, enables cost effective high throughput transport. American Petroleum Institute (API) grade pipeline steels that are employed for the pipeline transport of oil and gas are often considered for the transport of dense phase CO2 because of their reliability and low cost.

In general, pure CO2 is inert, stable, and non-corrosive. However, anthropogenic CO2 contains various impurities, such as water, sulphur oxides, nitrogen oxides, hydrogen sulphide, and carbon monoxide. If local pipeline conditions (e.g., temperature/pressure) decrease the solubility of water in CO2, condensation can take place and subsequently CO2 and gaseous impurities can dissolve in the condensed water, resulting in an acidic corrosive medium with pH less than 3.5. This leads to corrosion of many pipeline steels and the integrity of the pipeline can be compromised, potentially resulting in leakage or explosion. Understanding the factors controlling corrosion of pipeline steels in the dense phase CO2 environment is essential for qualifying pipeline materials for service and establishing reliable and cost-effective impurity threshold specifications.

NPL’s presentation gave a comprehensive overview of the most common experimental methodologies used to assess corrosion of pipeline steels in dense phase CO2. The current understanding of the corrosion of pipeline steels in dense phase CO2 and recommendations on future directions were also provided.

The Offshore Wind Session commenced with an online presentation by Anthony Setiadi, Wood Thilsted Partners, on the ongoing challenges in corrosion protection of foundations for offshore wind technologies.

he offshore wind industry growth is rapidly accelerating as the world is pushing towards renewable energy sources. Wind turbines often need to be installed on foundations which are in aggressive environments that are prone to corrosion if not protected and / or designed with corrosion in mind. There are various offshore wind foundation types, such as, monopiles, jackets, tetrabases, gravity bases and floating structures, often grouped in vast arrays for reasons of economy.

The presentation was primarily focused on monopile foundations and the design considerations that would need to be taken onboard. Monopiles have both internal and external surfaces needing protection. Coating requirements and different cathodic protection systems (i.e. galvanic and ICCP) were discussed for the internal

and external of the MP. Challenges regarding positioning of the CP system and installation concerns need to be considered along with any simultaneous operations that need to happen offshore during the installation phases e.g. piling operations that limit placement of anodes on the primary structure.

The main consideration is how the structure would behave with and without corrosion protection, especially the fatigue critical components such as the girth welds. The other consideration would be the site condition which will vary across the wind farm location and in some cases, a clustering strategy for varying sets of marine and geological conditions may be needed.

A corrosion protection plan must be developed and agreed well in advance, which then needs to be followed through to completion, including input to operation and maintenance strategies to ensure that the structure integrity is not compromised throughout design life.

Continuing on the corrosion protection theme, and presenting in person, Simon Daly Consultant – Energy & Infrastructure, (Safinah Group) discussed the many challenges for selecting protective coatings for fixed and floating wind industry.

Offshore wind turbine structures are exposed to environments with high salinity, high levels of UV radiation, the presence of cathodic protection and other factors. As well as the offshore turbines themselves, larger offshore structures such as transformer stations may have more extensive coating requirements including the need for passive fire protection. As the industry transitions to floating structures, designs may also have the challenges associated with marine fouling as well as more extensive coating work scopes.

With longer design lives required for current and future renewable type assets, more dedicated specifications are being developed, however some challenges exist ensuring proper execution of the specification during aggressive construction schedules. Given the costly nature of offshore recertification, this is also an area which requires constant attention to detail to minimise future expenditure.

Corrosion issues within existing fixed wind turbine facilities have highlighted coating requirements more extensive than previously foreseen. Different long term performance requirements, coupled with increased productivity to meet offshore renewables targets, means that coating selection must be carefully considered. Furthermore, with an increased focus on floating wind structures which have additional coating requirements and challenges to consider, the presentation discussed, the types of offshore structures used in wind power generation, different corrosive categories found internally and externally, an overview of corrosion protection issues experienced in fixed bottom structures, existing specifications used in coating selection, and how they differ between fixed and floating wind structures. A comparison of specifications currently used in offshore wind such as NORSOK M-501, DNV, NACE, VGB/BAW as well as development of future specifications, was explained.

This comprehensive presentation concluded with suggestions on how better integration of coating planning and activities throughout the lifecycle of an asset can help to reduce costs associated with coating and related activities.

In the Solar, Nuclear and Fusion Energy Session, Joven Lim – UK Atomic Energy Authority, dealt in great detail with the corrosion challenges in developing a Tokamak-type Fusion Reactor.

With the increase of national interest in developing and deploying clean energy and ensuring a good energy mix for the future, a fusion power plant is one of the ideal candidates. Fusion does not release carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Its major by-product is helium gas. Nuclear fusion reactors do not produce high activity, long-lived nuclear waste. The recent record-breaking 59 megajoules of sustained fusion energy demonstrated potential of fusion to be part of the future energy mix at the world-leading Joint European Torus facility, a Tokamak-type fusion reactor design, in Oxford, UK [https://www.euro-fusion.org/news/2022/european-researchers-achieve-fusion-energy-record/].

Like any other thermal power plant, coolant(s) will be used to transfer heat energy generated from fusion reactions and converted to electrical energy. With the knowledge gained from other power plants, and research studies performed in the past, it is feasible to predict and identify the potential corrosion challenges in a Tokamak-type fusion reactor.

In his presentation, the speaker gave a thorough overview of the Tokamak-type fusion reactor design, the potential list of coolants that can be used and why, and the expected corrosion challenges from the extreme environment in the reactor. The speaker also provided some insights on the criteria used for materials selection, corrosion management and mitigation strategy currently being developed for UK STEP fusion programme that aims to deliver a prototype fusion energy plant, by 2040 (https://step.ukaea.uk/).

Bringing the proceedings to a close, after an excellent and well-rounded full day event, Dr Frederick Pessu, University of Leeds, neatly summarised the corrosion challenges and related opportunities in arduous next generation low carbon energy systems (solar and nuclear energy).

Solar and nuclear energy sources have shown the greatest promise overall in worldwide efforts to meet the global climate change target. Electricity generation from solar and nuclear irradiation can be achieved using concentrated solar power (CSP) technologies and Gen IV molten salt nuclear reactors (MSR). Central to both CSP and MSR technologies is the use of high boiling point molten salts (MS) as heat transfer fluid, thermal energy storage and coolants (particularly for MSRs). Thus far, CSPs has played a significant role in delivering large-scale solar thermal electricity generation from photothermal conversion, due to its potential high efficiency, low operation cost and low environmental impact. CSPs promise to contribute up to 27% of global energy by 2050. Gen IV MSRs which are due for commercialisation in 2030 aim to deliver nuclear electricity at about 700°C by 2030, particularly as nuclear electricity is likely to see a 25% contribution to the UK energy mix.

The extreme conditions, high temperature (about 700°C) and aggressive corrosion media in MS systems do however pose complex material degradation issues related to corrosion, chemical speciation kinetics, high temperature fatigue and irradiation induced creep to conventional alloys. The need for advanced material systems/interfaces is timely, especially as the UK’s “green economic revolution” aims to increase nuclear electricity fourfold, achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and fully decarbonise by 2050. The presentation highlighted the corrosion challenges in the new frontier of low carbon and renewable energy generation, solar and nuclear energy, and state – of – the – art understanding of the underpinning mechanisms. Opportunities for research-led development of new material system, interfaces, and technologies for UK businesses were fully discussed.

Presserv Ltd, the sponsor of this Net-Zero event, gave a demonstration of STOPAQ environmentally friendly products and their application on a pipe section, in the reception area.

There are bonus online pre-recorded presentations included as part of the programme which can be viewed online in the ICorr Members site,

• Selection of coating material in oil and gas industries and use of advanced coating processes for corrosion protection in present industrial scenario. Urvesh Vala, Chiyoda Ltd India.

• The use of magnetic probe couple to augment existing equipment and technology. Jonathan Francis, Trac Energy Presentation.

This most successful event, which raised nearly £3,000 for ICorr training funds, was followed by an evening event with the President – Bill Hedges.

ACF Dinner with Bill Hedges.

The branch gratefully acknowledges the support of all the ACF participants and the ICorr HQ Admin Team.

Event photos and slides can be viewed at: https://1drv.ms/u/s!Ajj3m1kM8SgPrj_TTl_bylOPF1LB?e=EfsRMM.

The Aberdeen Branch has now formed a new committee for 2022-2023 session under the chair of Dr Muhammad Ejaz. Supporting him in the Vice Chair role will be Adesiji Anjorin, the previous events co-ordinator. The full committee are their responsibilities can be found on the branch page of the website.

Welcome to the autumn issue of your magazine, and it is another bumper issue. There is an extensive Institute News section, with information on the upcoming AGM and details of a new training course. There are the usual Fellow’s Corner and Ask the Expert columns, but slightly shorter than normal to make way for the three technical articles. These cover improving the life of anodes, bottom plate corrosion of above ground storage tanks, and a very interesting look at the effect of climate change on carrion from Chris Atkins.

As you will have seen from the “President Write” column above, I have decided to stand down as editor, so this should be my penultimate issue. After being editor for 6 years, and working in the industry for more than 50 years, it’s time for me to relax and enjoy retirement.

It has been a pleasure to produce the magazine, and I hope you have enjoyed reading it.

Brian Goldie, Consulting Editor

Email: brianpce@aol.com

This series of articles is intended to highlight industry wide engineering experiences, practical opinions and guidance, to allow improved awareness for the wider public and focused advice to practicing technologists. The series is written by ICorr Fellows who have made significant contributions to the field of corrosion management. The articles in this issue feature contributions from Bijan Kermani and Dmitry Sidorin.

An overview materials optimisation in CCS

A net-zero energy system to hinder or mitigate global warming driven by burning fossil fuel requires a step change in the way energy is being produced and used. This can only be achieved with a broad suite of technologies including improved energy efficiency, introduction of renewable energy and nuclear power. No mitigation option alone will achieve the desired reduction targets, however, they can be made

more influential when complemented by carbon capture and storage

(CCS) process.

CCS with sequestration can contribute both to reducing emissions and to removing CO2 to balance emissions – a critical part of “net” zero goals. CO2 sequestration is a process by which CO2 is removed from the atmosphere and stored indefinitely in underground locations primarily by means of pipelines. In addition to political and environmental incentives, CO2 sequestration is being considered in tertiary recovery for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) to produce residual hydrocarbon. Many oil and gas operators are looking at materials optimisation for such applications.

This Fellow’s Corner combines current status of corrosion threats and materials options for CO2 pipeline transmission and includes a simple roadmap enabling materials optimisation and outlining any technology gaps that may exist. It starts by describing sources of CO2, means of capture, methods of transportation and sequestration.

Sources of CO2, Capture and Sequestration

CO2 emission arises primarily from human activity and mainly from the combustion of fossil fuels used in different industrial sectors. CO2 is also emitted during certain industrial processes like cement manufacture or hydrogen production and during the combustion of biomass.

The first step in sequestration is CO2 capture. This is done through potentially numerous schemes, some commercially available at present, but all with a significant cost penalty. Capture from the atmosphere is done through biological, chemical or physical processes. The capture system may conveniently be divided into three categories (i) post combustion capture (scrubbing), (ii) pre-combustion capture and (iii) oxyfuel capture, details of which are beyond the scope of the Fellow’s Corner.

Having captured CO2, it needs to be transported and stored for long periods. This can be achieved by sequestration, a process by which CO2 removed from the atmosphere is injected and stored indefinitely. There are currently more than 70 CO2 injection projects in the US, injecting more than 35 million tons of CO2 annually, primarily for EOR.

Briefly, sequestration methods includes (i) geological sequestration, (ii) CO2 EOR, (iii) deep ocean sequestration, (iv) mineral and biological sequestration and (v) terrestrial sequestration again, details of which are beyond the scope of the Fellow’s Corner.

While CO2 has been injected into various geologic formations for decades for EOR purposes and acid gas disposal, the idea of permanent CO2 storage, or sequestration, for the purpose of mitigating global climate change is a fairly novel one with few commercial-scale prototypes upon which to draw guidance in the development of a regulatory framework.

Means of Transportation

Once captured and compressed, CO2 must be transported to a long term storage site as schematically shown in Figure 1 (below). In principle, transmission may be accomplished by pipelines, tankers, trains, trucks, compressed gas cylinders, as CO2 hydrate, or as solid dry ice. However, only pipeline and tanker transmission are reasonable economical options for the large quantities of CO2 associated with, for example, a 500MW power station. Trains and trucks could be used in the future for the transport of CO2 from smaller sources over short distances.

Pipelines

CO2 transmission by pipeline and injection into reservoirs began several decades ago. More than 40 million tons per year of CO2 are currently transmitted through high pressure CO2 pipelines, mainly in North America. Most of the CO2 obtained from natural underground sources is used for EOR.

The Weyburn pipeline, which transports CO2 from a coal gasification plant in North Dakota, USA to an EOR project in Saskatchewan, Canada is probably the first demonstration of large-scale integrated CO2 capture, transmission, sequestration and storage.

Ship Tankers

Ships are now used on a small scale for the transport of CO22 . Large scale transport of CO2 from power stations located near appropriate port facilities may occur in the future.

CO2 would be transported as a pressurised cryogenic liquid, for example at approximately 6 bar and -55°C. Ships offer increased flexibility in routes, avoid the need to obtain rights of way, and they may be cheaper, particularly for longer distance transportation. Ships similar to those currently widely used for transportation of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and liquefied natural gas (LNG) could be used to transport CO2.

Corrosion Threats and Severity

Dry CO2 is non-corrosive and relatively easily handled using conventional grades of carbon and low alloy steels (CLASs). However, in the presence of water, the situation is more complicated and system corrosivity would depend on water solubility of the CO2/H2O mixture and therefore, materials used in CCS systems can be subject to corrosion threats in which materials optimisation can take a centre stage.

CO2 readily dissolves in water to form carbonic acidic solution that is highly corrosive to many engineering materials. The accelerating effect of CO2 corrosion is a particularly important safety issue when considering the maintenance schedules and operating life expectancies for pipelines that were not originally designed for CO2 transmission use. Choice of materials for handing CO2 is governed by many parameters including physical state of CO2, water content, its purity and level and nature of impurities.

An additional complicating parameter is the presence of H2S and other potential impurities. A limit on the concentration of H2S is important for two complementing reasons including (i) the likelihood of exceeding sour service limits of materials and (ii) as H2S and O2 may lead to the formation of elemental sulphur which makes system corrosivity even more complex. It should be noted that the presence of small amount of water leads to increasing the iron concentration and pH which results to a low corrosion rate. However, this is difficult to predict and quantify.

High levels of CO2 in the CCS process places the operating conditions beyond the limits of existing CO2 corrosion predictive models and in majority of cases application specific testing may be required. Nevertheless, published data by Institute for Energy (Norway) and Ohio University (USA) indicates that in a condition where CO2 is more than around 50 bar, corrosion rate of CLASs can be estimated to be around 1/10 that predicted by conventional corrosion prediction models.

Materials Optimisation Guidelines

The first step in a systematic materials optimisation process, is to explore the feasibility of using CLAS as it offers satisfactory mechanical properties and economy, although has poor corrosion resistance. System corrosivity assessment therefore is necessary to establish the likelihood of success in using CLASs an area in need of fine tuning. Here a broad guideline is given for handling CO2.

CO2 Only

CO2 can exist in variety of physical states depending on the temperature and pressure. The physical state of CO2 and respective approach to materials selection for CO2 transmission in form of a guideline is shown in Figure 2. The guideline is divided into five conditions depending on the physical state of CO2.

The guidelines in Figure 2, excludes the effect of contaminants (H2S, O2, SOx) and applicability limit for H2O as there are no systematic data on these parameters.

It is apparent that successful utilisation of CLAS is highly dependent on the absence of water and other impurities in which thermodynamic analysis to confirm absence of water throughout the pipeline or tubing over the operational life is essential.

CO2 and Oxidizing Agents

CO2 transmission in the presence of oxidizing gases such as SO2, SO3 and O2 becomes even more complicated. Again in the absence of water, there is no likelihood of corrosion. However, in the presence of water, a combination of oxidizing species (SO2, SO3 and O2) and acidic gases (CO2 and H2S), likelihood of corrosion becomes a serious issue. In such situations, a more prudent approach should be adopted and thermodynamic analysis to ensure lack of water throughout the system and design life becomes even more essential. In practice, injection of CO2 with oxidizing agents should not be contemplated unless proven otherwise. The option is to either remove the oxidizing agents, implement total dehydration or the use of an appropriate grade of corrosion resistant alloy (CRA).

References

1. B Kermani and D Harrop, Corrosion and Materials in Hydrocarbon Production; A Compendium of Operational and Engineering Aspects, Wiley, 2019.

2. Carbon Capture, Transportation, and Storage (CCTS), Aspects of Corrosion and Materials, ed B Kermani, NACE International, 2013.

![]()

Figure 2 – Materials option guideline for CO2 sequestration.