Meet The Authors

Introduction

The year 2024 marks the 200th anniversary of the first two of three remarkable papers [1-3] by Sir Humphry Davy describing the earliest scientific investigations into what we now call cathodic protection (CP). Although the word “cathode” was not in use until proposed by Michael Faraday in 1834 [4], this paper will keep using the modern abbreviation “CP” for convenience. Similarly, Faraday also proposed using the word “anode” in his 1834 paper and we will call the anodic metals used by Davy as anodes, rather than “protectors”.

Davy presented three seminal papers to the Royal Society in London, beginning with his first on January 22, 1824 [1] giving the scientific reasons, background and laboratory research results for the application of CP to prevent corrosion of copper sheeting on timber ships in seawater. His second paper describing additional experiments and observations for copper sheeting on vessels in Chatham and Portsmouth Navy dockyards was presented on June 17, 1824 [2] and his third paper detailing full scale research and results for ships on the high seas was read on June 9, 1825 [3].

There was controversy then, as there is now, about some aspects of Davy’s work [5, 6]. This paper discusses some of these issues and demonstrates that Davy was well aware of any shortcomings but importantly, he also suggested possible solutions to overcome the occasional problem of an increase in fouling of the copper sheet under specific circumstances [3, 7]. Notably, the application worked unambiguously to prevent corrosion of the copper in all cases, with fouling only occurring on some vessels and Davy was in the process of understanding the differences in operational circumstances. It will be shown that it was primarily a loss in funding and a wish by the British Admiralty (after pressure from some ship’s captains and the media) for quick solutions that cut short further investigatory work after just two years (i.e. 1823 to 1825). It was left to future scientists and engineers to show how CP could be used effectively and efficiently to protect any metal or alloy immersed in an electrolyte, including even reinforced concrete [8]. When reviewing his work, it must be seen in the context of the scientific understanding of electrochemical processes at the time. For instance, Davy was able to formulate the principles and application of CP decades before the electron was discovered by J.J. Thomson in 1897 and long before chemical and electrochemical reactions were written in the format used today. Judging his discoveries against modern principles is unfair at best and anyway, he was spot-on about plenty of technical points, as will be seen.

Previous Discoveries Leading to Davy’s Understanding of Electrochemical Processes and “Cathodic Protection”

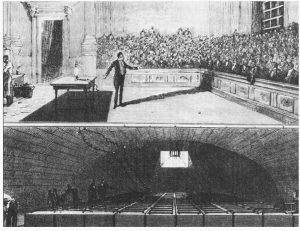

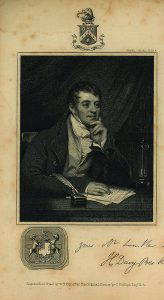

Humphry Davy quickly adopted and contributed to the electrochemical technology developed by luminaries such as Luigi Galvani [9], Alessandro Volta [10], Nicholson and Carlisle [11] and others. An example of the terrific electrical power he was able to produce can be seen in Figure 1 which shows the battery banks below a lecture theatre where he was demonstrating electric arc lighting. The portrait of Davy in Figure 2 includes a typical Voltaic pile (typically consisting of alternating stacks of brine-soaked cards sandwiched between pieces of copper and zinc or other combinations of dissimilar metals), a common feature in portraits of electrochemical scientists.

This background placed Davy in a perfect position to investigate a costly corrosion issue for the British Navy. In 1822, Davy was first approached by the British Navy Board to provide advice regarding the corrosion of copper sheeting on the Royal Navy’s timber ships [5]. The copper sheeting was effective at protecting the ships’ timber from worms and preventing the growth of “weeds” which otherwise had the effect of slowing the ships movement through the water. Davy read the board’s letter to the Council of the Royal Society of which Davy was President. The Council formed a committee (with Davy as President) to investigate the matter and decided to test copper specimens supplied by the Navy. Davy eventually dispensed with the committee and began working personally on the problem in 1823, reported directly to the Admiralty on 17th January 1824 and then read a groundbreaking paper to the Royal Society on 22th January 1824.

Davy’s Paper of January 22nd, 1824

This, Davy’s first paper on CP, proves the ability of CP to prevent corrosion. There may well be other consequences, but the beneficial effect upon corrosion was unambiguously proven and is not in dispute.

Let’s look at some of the key issues raised in this first paper:

Davy, along with his assistant Michael Faraday, proved incorrect the general supposition at the time that the “rapid decay” (i.e. corrosion) of copper was due to impurities, surmising that “pure” copper was acted upon more rapidly than the specimens which contained alloy (although the type of alloying was not provided) and that “changes” (corrosion) in various specimens of ships copper collected by the Navy Board “… must have depended upon other causes than the absolute quality of the metal”. The quality of the metal is important but other factors were also believed by Davy to play a critical role including “temperature, the relative saltness (sic.) of the sea, and perhaps the rapidity of the motion of the ship; circumstances in relation to which I am about to make decisive experiments” [2].

Davy described “the nature of chemical changes taking place in the constituents of sea water by the agency of copper” and especially the importance of oxygen in the process.

Davy repeats his hypothesis from 1807 [12] (read 20 November 1806) “that chemical and electrical changes may be identical”; a feature clarified and enumerated by his assistant Michael Faraday [4] several decades later with what is now popularly called Faraday’s Law of electrochemical equivalence [4]. Davy then describes how, by this hypothesis, “that chemical attractions may be exalted, modified or destroyed, by changes in the electrical states of bodies”. In other words, change the electrical state from its natural positive or negative state (i.e. change the potential, another word not yet in electrochemical use) and you will cause the chemistry to change. Davy then notes that it was the “application of this principle that, in 1807, I separated the bases of the alkalies from the oxygene with which they are combined and preserved them for examination; and decomposed other bodies formerly supposed to be simple”.

All of these past works by Davy led him “to the discovery which is the subject of this Paper”.

It is a testament to Davy’s scientific method that he supported his hypothesis by past research results, created an understanding of the processes involved and then went on to test it in the laboratory and with full scale trials, collecting and analysing the data for comparison with the predictions of the hypothesis.

Once he had established the basis of his hypothesis, he went on to suppose that if copper “could be rendered slightly negative, the corroding action of sea water upon it would be null; (i.e. polarise the copper negative) and whatever might be the differences of the kinds of copper sheeting and their electrical action upon each other (i.e. galvanic effects), still every effect of chemical action must be prevented, if the whole surface were rendered negative” He then astoundingly says “But how was this to be effected? I first thought of using a Voltaic battery; but this could be hardly applicable in practice”. So, Davy first thought of using an impressed current CP system! He could hardly know that future DC power supplies would make impressed current an easy and common means of cathodically polarising a structure. Davy then says “I next thought of the contact of zinc, tin, or iron”; i.e. galvanic anode CP.

Davy, assisted by “Mr Faraday” then conducted a series of experiments using these three metals to mitigate corrosion on copper. He then reports that although tin was initially effective, “it was found that the defensive action of the tin was injured, a coating of sub-muriate (chloride compound of tin) having formed, which preserved the tin from the action of the liquid”; the tin chloride deposits reduced the effectiveness of tin as an anode. “ With zinc or iron, whether malleable or cast, no such diminution of effect was produced”. Davy now knew for certain that he had effective anodes for the galvanic CP of copper.

Davy and Faraday then proceeded to conduct numerous experiments using zinc and iron in various shapes and sizes attached to copper, including small pieces “as large as a pea”, wires, nails, sheets connected directly by wires, filaments, soldering etc, and always with areas of zinc or iron much smaller than the copper being protected.

Near the end of the paper Davy notes “…. that small pieces of zinc, or which is much cheaper, of malleable or cast iron, placed in contact with the copper sheeting of ships, which is all in electrical connection, will entirely prevent its corrosion”. It is an important note by Davy that the iron anodes were much cheaper, and we will return to this issue when discussing the next two papers presented to the Royal Society.

Finally, Davy says that in future communications he might describe other applications that the principle can be used “to the preservation of iron, steel, tin, brass, and various useful metals”. He was definitely aware that

the principle is widely applicable to any metal or alloy, a feature we enjoy today [13].

Davy’s Paper of June 17th 1824, Additional Experiments and Observations

Davy reports the results of sheets of copper connected to zinc, malleable and cast iron for many weeks in Portsmouth Harbour. He notes that cast iron, which is the cheapest and most easily procured of the materials tested “is likewise most fitted for the protection of copper” and lasts longer than malleable iron or zinc. Davy later however, after further research, recommends a preference to use zinc anodes rather than iron [3].

Davy anticipated and observed “the deposition of alkaline substances” on the copper being “carbonated lime and carbonate and hydrate of magnesia”. Nicholson and Carlisle had discovered the decomposition of water using a voltaic pile [11] (described by Davy as a “capital fact” [7]) and included a description of “the separation of alkali on the negative plates of the apparatus”, hence Davy’s anticipation. These now familiar calcareous deposits of calcium carbonate and magnesium hydroxide are crucial to

the efficiency of CP systems in seawater. Davy was clearly aware of the increase in alkalinity at the cathode and acidification at the anode.

(Note: Even though the concept of pH and the quantification of acidity

and alkalinity was not formulated until 1909 [14], Davy talks extensively about the alkalinity and acidity produced during galvanic coupling of different metals).

Davy also understood and documented that when the calcareous deposit completely covered the copper sheets, it could result in “weeds” and “insects” collecting on them. Davy then considers the amounts of calcareous deposits generated by various quantities of anode material. He found that using zinc and iron anode to copper area ratios from 1/35 to 1/80, the copper became coated with calcareous deposits but “weeds” eventually adhered to the surface as well. He then reports that when the ratio was reduced to 1/150 “… the surface, though it has undergone a slight degree of solution, has remained perfectly clean; a circumstance of great importance as it points out the limits of protection; and makes the application of a very small quantity of the oxidable metal, more advantageous in fact than that of a larger one”. So, Davy here cautions about the excessive application of anodes for the specific protection of copper in seawater when fouling is unwanted and illustrated that fouling could also be mitigated if careful selection of the anode quantities was made for the specific circumstances in which they were used.

Davy’s Paper of June 9th 1825, Further Research

Davy’s full-scale trials were generally very successful, certainly he prevented the copper corrosion, and he makes the comment that the fouling was usually not an issue if the vessel is on the move. He notes that mooring stationary in harbour allows calcareous deposits to form more readily (surface pH will rise more than when in motion) and weeds etc can adhere. He also mentions the quality of the copper may be important and that the proportion of the anode: cathode area ratio affects deposits.

He observed that the marine growths are often initiated on the iron oxides deposited near the anodes (“protectors’’); he recommends here a preference to use zinc anodes rather than iron, “Zinc, in consequence of its forming little or no insoluble compound in brine or seawater, will be preferable to iron …”

Davy defends his work from page 341 onwards in his 1825 paper where he says “A false and entirely unfounded statement respecting this vessel (the 28-gun “Sammarang”) was published in most of the newspapers, that the bottom was covered in weeds and barnacles. I was present at Portsmouth soon after she was brought into dock: there was not the smallest weed or shell-fish upon the whole of the bottom from a few feet round the stern protectors to the lead on her bow.” He goes on to describe other instances of fouling and non-fouling when protected and at least attempts to understand the various circumstances.It appears that cast iron anodes were used in most of the field trials on ocean-going copper sheathed ships. For instance, Davy states in the Bakerian Lecture of 1826 (p. 420) [7], when discussing the field trials and operations “… in the only experiment in which zinc has been employed for this purpose in actual service, the ship returned … perfectly clean”. Davy wanted to conduct further experiments on ships in service, because the mitigation of corrosion was proven and fouling only occasional for reasons he thought could have been elucidated by further work.

It seems reasonable to expect the vessel captains, wanting the most from the protection system, to add iron anodes at possibly excessive rates since they were relatively cheap, easily procured and then complain that fouling was unacceptable. This is corroborated by Davy’s observation [3] when discussing several ships returned from the West Indies that “The proportion of protecting metal in all of them has been beyond what I have recommended, 1/90 to 1/70; yet two of them have been found perfectly clean, and with the copper untouched after voyages to Demarara; and another nearly in the same state, after two voyages to the same place. Two others have had their bottoms more or less covered with barnacles; but the preservation of the copper has been in all cases judged complete”. Davy was therefore not reluctant to report fouling on some ships but balanced this with positive reports. Clearly it was possible to obtain both corrosion protection and no fouling; it would just require continued methodical research (and with ship owners/captains installing the recommended quantities of anodes rather than excessive amounts).

On the issue of fouling, F. James’ otherwise excellent article on Davy [5] claims that “Davy does not seem to have appreciated the side effect, and he was certainly unable to overcome it”. This is incorrect on two points; Davy did appreciate the issue if one refers to the scientific articles as we have above where Davy addresses this specific issue and he was in the throes of trying to better establish the conditions in which corrosion mitigation and acceptable amounts of fouling could be achieved. Unfortunately, ongoing pressure finally led the Admiralty to issue orders to the Navy Board on 19 July 1825 to discontinue the project [5], thus ending further research just two years after first being initiated. The historian S. Ruston, in an essay discussing Davy as the philosopher [6], seems to draw heavily on James’ article where Ruston writes “Unfortunately, what had worked in the laboratory did not work at sea …”. This is incorrect since there was no disputing that the corrosion was fully mitigated; it worked perfectly well and was the original aim of the Admiralty’s directions, with only fouling being a troublesome and sometimes unacceptable side effect. On this Ruston goes on to write “…the electro-plating (sic.) had a chemical side effect, which stopped the poisonous copper salts from going into the sea and resulted in ships’ bottoms being fouled thus slowing them considerably”. Although Ruston mistakes electrochemical protection used by Davy as “electro-plating”, the essay ignores the actual scientific words of Davy within his papers to the Royal Society where, as discussed above, he understood the effect of calcareous deposits, the effect on fouling and the need to strike a practical balance between corrosion protection and fouling.

There was a lot riding on Davy’s work and competition from other inventors tied with the newspapers [5]. Plenty of “fake news” and “alternative truths” – not much has changed! If we study these works with our scientific, objective eyes we can establish a good understanding of the success or otherwise of Davy’s work. Davy makes so many great and insightful statements about his observations, many of which are equally valid today. Also don’t forget that he had the greatest assistant one could imagine in Michael Faraday in these works. The veracity of Davy’s publications is not in doubt, especially with Faraday on board.

Today’s Navy

The world’s navies to this day use cathodic protection on virtually every ship, submarine and marine vessel on the oceans and waterways across the globe to mitigate corrosion, both external to the hull and within internal water filled spaces [15-17]. Ships hulls are of course now predominantly coated steel, but Davy would surely have been pleased to know that zinc anodes are still used extensively as shown in Figure 3, using the same basic principles [17]. Impressed current systems are used for larger current demand applications on bigger vessels but even these are often supplemented with zinc anodes around high current demand areas and shielded locations such as sea chests, ballast tanks, propellers or shafts. Aluminium alloy anodes also provide excellent, cost-effective performance in seawater, but zinc is especially versatile when vessels experience waters of varying salinity such as estuaries and harbours with freshwater inflow.

Conclusions

Although the intent of this paper is to focus on Davy’s work, it is important to note that in the decades and now centuries following Davy’s work extraordinary advances were made in the understanding of the science that underpins CP [13, 18, 19], amongst other fields of science and engineering, this included:

•Michael Faraday’s discovery and experimental proof about the electrochemical equivalence between electric current and corrosion already mentioned.

•Josiah Gibbs’ development of the thermodynamics that lets us determine whether an electrochemical reaction can occur.

•Julius Tafel’s investigations and descriptions during the 1890’s and early 1900’s about how changes in the metal potential can regulate the anodic and cathodic reaction rates and

•Walther Nernst who showed how the potential of a metal could be calculated if the concentrations of reactants and products were known and in doing so, the stability of chemical species could be predicted if the potential and pH were known.

•Marcel Pourbaix summarised all of these features into his first beautiful Pourbaix diagrams [20, 21].

•Mears and Brown [22] also provided a clear kinetic description of CP in 1938 that is still valid today.

•R. J. Kuhn [23, 24] first suggested the earliest criterion for CP of polarising to -0.85 VCSE or more negative, which was shown to be suitable for steel, not only in seawater [25] but also in soils [26].

The increase in pH at the metal surface [27] and the subsequent development of passive oxide films during cathodic polarisation and their role in mitigating corrosion for steel, when considering both the kinetics and thermodynamics, is now well established for iron and steel alloys [28-30] and our deeper understanding continues to evolve, as good science always does.

Role of Calcareous Deposits

•It was recognised very early on [31] that the primary protective action of the calcareous deposits is to; (i) act as a barrier to oxygen or other depolarisers, (ii) increase the internal resistance of the local corrosion cells and (iii) increase the pH of the water film in contact with the metal surface above that of normal seawater. The benefits to marine cathodic protection systems are now well known, particularly in reducing the current density requirement for corrosion mitigation [31-35], a feature reflected in various industry standards for marine structures [36-38].

•The formation of calcareous deposits anticipated and observed by Davy is also still of special interest today and the circumstances of their formation continue to be investigated [17, 39]. R. J. Kuhn [24] also noted the formation of calcareous deposits that varied from “… practically nothing in neutral areas to an inch in thickness in heavily drained areas”, and hence in the degree of the protective or beneficial efficiency.

•The calcareous deposits formed by CP can also have detrimental effects such as accelerated bearing wear in water-lubricated propeller shafts and seizing of hull valves due to clogging [17], or in non-seawater applications such as limiting heat transfer of pumps causing overheating. Means of avoiding these adverse effects continue to be investigated [17], along with understanding the effects of CP upon biofouling [40].

Davy achieved remarkable success even though after 200 years, issues with the protection of metals and alloys using CP are still the subject of ongoing research and refinement. The future remains bright, with vigorous research continuing worldwide into CP, advancing the science and range of applications to an ever-widening array of structures. Science never sleeps and no doubt each new generation of scientists and engineers will, bit by bit, keep adding to our knowledge and advance Davy’s legacy.

References

1. Davy, H. (1824) OVI. On the Corrosion of Copper Sheeting by Sea Water, and on Methods of Preventing This Effect; and on Their Application to Ships of War and Other Ships. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 114 January 22, 1824 151-158

2. Davy, H. (1824) XII. Additional Experiments and Observations on the Application of Electrical Combinations to the Preservation of the Copper Sheathing of Ships, and to Other Purposes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 114 June 17, 1824 242-246

3. Davy, H. (1825) XV. Further Researches on the Preservation of Metals by Electrochemical Means. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 115 June 9, 1825 328-346

4. Faraday, M. (1834) On Electro-chemical Decomposition, continued (part of Experimental Researches in Electricity – Seventh Series). Philisophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 124 77-122

5. James, F. A. J. L. (1992) Davy in the dockyard: Humphry Davy, The Royal Society and the electrochemical protection of the copper sheeting of His Majesty’s ships in the mid 1820s. Physis 29 205-225

6. Ruston, S. (2019) Humphry Davy: Analogy, Priority and the “true philosopher”. AMBIX 66 (2-3, May-August) 121-139

7. Davy, H. (1826) The Bakerian Lecture. On the relations of electrical and chemical changes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 116 383-422

8. Cherry, B. and Green, W. (2021) Corrosion and Protection of Reinforced Concrete, CRC Press

9. Galvani, L. (1791) De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius (A Commentary on the Powers of Electricity in Muscular Motion). De bononiensi scientiarum et atrium instuto atque academia Commentarii 7 363-418

10. Volta, A. (1800) On the Electricity Excited by the Mere Contact of Conducting Substances of Different Kinds. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 90 403-430

11. Nicholson, W. (1800) Account of the Electrical or Galvanic Apparatus of Sig. Alex.Volta and Experiments performed with the same. Nicholson’s Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts 4 (July) 179-191

12. Davy, H. (1807) The Bakerian Lecture, on some chemical agencies of electricity. Philisophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 97 1-56

13. Ackland, B. G. (2012) Cathodic Protection – It Never Sleeps. In: Corrosion and Prevention 2012, Plenary no. 4, Melbourne: 11-14 November 2012, Australasian Corrosion Association

14. Sörensen, S. P. L. (1909) Enzymstudien. II. Mitteilung. Über die Messung und die Bedeutung der Wasserstoffionenkoncentration bei enzymatischen Prozessen [Enzyme studies. 2nd Report. On the measurement and the importance of hydrogen ion concentration during enzymatic processes]. Biochemische Zeitschrift (in German) 21 131-304

15. Morgan, J. (1987) Cathodic Protection. Second ed, National Association of Corrosion Engineers, Houston, Texas

16. von Baeckmann, W., Schwenk, W. and Prinz, W. (1997) Handbook of Cathodic Corrosion Protection, Gulf Professional Publishing

17. Dylejko, K., Neil, W. (2024) Plenary Lecture – Cathodic Protection and its Implications for Vessels in the Royal Australian Navy. In: Australasian Corrosion Association Conference 2024, Cairns, Australia

18. Ackland, B. G. (2005) P.F. Thomson Memorial Lecture – Cathodic Protection – Black Box Technology? In: Corrosion and Prevention 2005, paper no. 4, Brisbane, Australia, Australasian Corrosion Association

19. Martinelli-Orlando, F., Mundra, S. and Angst, U. M. (2024) Cathodic protection mechanism of iron and steel in porous media. Communications Materials 5 (1) 2024/02/16 15

20. Pourbaix, M. (1945) Thermodynamique des solutions aqueuses diluées. Représentation graphique du rôle du pH et du potentiel. Delft

21. Pourbaix, M. (1974) Atlas of Electrochemical Equilibria in Aqueous Solutions, National Association of Corrosion Engineers

22. Mears, R. B. and Brown, R. H. (1938) A Theory of Cathodic Protection. Transactions of The Electrochemical Society 74 (1) January 1, 1938 519-531

23. Kuhn, R. J. (1933) Cathodic Protection of Underground Pipe Lines from Soil Corrosion. API Proceedings 14 (Section 4) 153-167

24. Kuhn, R. J. (1928) Galvanic Current on Cast Iron Pipes – Their Causes and Effects – Methods of Measuring and Means of Prevention. In: Soil Corrosion Conference, Washington: December 10, Bureau of Standards

25. Schwerdtfeger, W. J. (1958) Current and Potential Relations for the Cathodic Protection of Steel in Salt Water. Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards 60 (3) March 1958 153-159

26. Schwerdtfeger, W. J. and McDorman, O. N. (1951) Potential and Current Requirements for the Cathodic Protection of Steel in Soils. Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards 47 (2) August 1951 104-112

27. Kobayashi, T. (1974) Effect of Environmental Factors on the Protective Potential of Steel. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on Metallic Corrosion, Houston, Texas, NACE

28. Angst, U., et al. (2016) Cathodic Protection of Soil Buried Steel Pipelines – A Critical Discussion of Protection Criteria and Threshold Values. Werkstoffe und Korrosion 67 (11) 1135-1142

29. Angst, U. (2019) A Critical Review of the Science and Engineering of Cathodic Protection of Steel in Soil and Concrete. Corrosion 75 (12) 1420-1433

30. Freiman, L. I., Kuznetsova, E.G. (2001) Model Investigation of the Peculiarities of the Corrosion and Cathodic Protection of Steel in the Insulation Defects on Underground Steel Pipelines. Protection of Metals 37 (5) 484-490

31. Humble, R. A. (1948) Cathodic Protection of Steel in Sea Water With Magnesium Anodes. Corrosion 4 (July) 358-370

32. Wolfson, S. L. and Hartt, W. H. (1981) An Initial Investigation of Calcareous Depsoits Upon Cathodic Steel Surfaces in Sea Water. Corrosion 37 (2) 70-76

33. Ryan, L. T. (1954) Cathodic protection of steel-piled wharves. Journal of the Institute of Engineers, Australia 26 (7) 160-168

34. Humble, R. A. (1949) The Cathodic Protection of Steel Piling in Sea Water. Corrosion 5 (September) 292-302

35. Hartt, W. H., Culberson, C. H. and Smith, S. W. (1984) Calcareous Deposits on Metal Surfaces in Seawater – A Critical Review. Corrosion 40 (11) 609-618

36. ISO 15589-2 Oil and gas industries including lower carbon energy — Cathodic protection of pipeline transportation systems, Part 2: Offshore pipelines. (2024).

37. DNV-RP-B401 Cathodic protection design. (2021).

38. AS 2832.3 Cathodic Protection of Metals Part 3: Fixed Immersed Structures. (2005).

39. Carre, C., Zanibellato, A., Jeannin, M., Sabot, R., Gunkel-Grillon. & Serres, A. (2020) Electrochemical calcareous deposition in seawater: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 18 1193-1208

40. Vuong, P., McKinley, A. & Kaur, P. (2023) Understanding biofouling and contaminant accretion on submerged marine structures. npj Materials Degradation 7 Article 50, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-023-00370-5