MEET THE AUTHOR

1. Introduction

Epoxy Passive Fire Protection (EPFP) systems are safety-critical coatings that are installed in high-hazard process facilities and sometimes also in public buildings. Their requirement is often driven by legislation and are considered of life-safety importance.

Epoxy Passive Fire Protection (EPFP) is designed to insulate critical steel structures from the temperature rise (heat) in a fire event. This safety-critical insulation function slows the temperature rise to maintain structural or pressure retaining integrity, giving time for emergency shutdown, inventory blowdown, and/or safe abandonment. Therefore, correct quality control activities during the whole installation process are critical; this is because the entire system holds a function but ultimately is only as strong as its foundation. For example, when the EPFP is applied to a galvanised surface, the galvanising itself becomes that foundation, and therefore, it’s critical that confidence (quality assurance) is demonstrated. If the galvanising fails, then the EPFP may become compromised.

Hot-dip galvanising creates a metallurgical bond between zinc and steel. When executed correctly on a properly prepared surface, this bond is incredibly robust. However, several factors in the galvanising process can create a weak and unreliable substrate that may be unsuitable for supporting a safety-critical EPFP system. It is crucial to understand that these issues are not restricted to EPFP alone; they are a fundamental concern for all high-build coating systems that rely on a strong foundation to function. An example of galvanised steel section with EPFP applied is shown below in Photo 1.

This article will explore:

1. The inherent risks associated with galvanising including excessive thickness, metallurgical defects, and inadequate repair methods that can compromise the bond and ultimately could detract from the overall durability of the system.

2. This article will argue that the best practice is the direct application of EPFP paint systems to properly prepared steel substrates as a correctly installed EPFP system can give a comparable durability range. Therefore, galvanising should only be considered as a substrate for EPFP when there are no other design options available, and even then, only with additional (stringent) quality control measures that may go beyond typical industry/project expectations. This article will explore the inherent risks associated with galvanising including excessive thickness, metallurgical defects, and inadequate repair methods that can compromise the bond and ultimately could detract from the overall durability of the system.

2. The Challenge with Galvanising

The ability of a galvanised coating to support an EPFP system can be severely impaired by several influencing factors:

•Excessive galvanising thickness: The primary source of impairment.

•Metallurgical defects: Inclusions and weak layers that may form during the galvanising process.

•Poor bonding: Initial or Inadequate surface preparation leading to a weak bond.

•Surface passivation: Post-galvanising treatments that can impair adhesion.

The “Thicker is Better” Concept

Standard galvanising specifications like ISO 1461 and ASTM A123 are written with no consideration that EPFP system may also get specified and are typically for corrosion protection, they do not consider any additional thick film coating such a EPFP system.

They often imply that exceeding the minimum with no consideration to maximum thickness is not a cause for concern. However, for EPFP applications, this is a dangerous misleading understanding. Experience has shown that as a galvanised coating thickness increases, its cohesive strength may decrease. The primary drivers for this excessive growth are the chemical composition of the steel—typically its silicon (Si) and phosphorus (P) content—and the thermal mass of the steel section [2].

• High Silicon and Phosphorus Content: Steel with high levels of silicon (particularly in the range of 0.04% to 0.14%, known as the “Sandelin range”) and phosphorus accelerates the growth of the zinc-iron alloy layers (eta, zeta, and delta).

• Uncontrolled Growth: Rapid growth results in a thick, brittle, and often friable zeta layer. Instead of a dense, tightly bonded coating, there is an increasing likelihood that a coarse crystalline structure which is inherently weak may result.

Therefore, a galvanised coating that is too thick—for example, exceeding 250 µm (microns)—may not be robust when coated with thick EPFP coatings. It may have micro-cracks and a high degree of internal stress resulting in voids and weak layers. When the EPFP is applied over this type of surface, the galvanised layer itself can delaminate due to stress imparted by the EPFP.

3.Setting Strict Limits

Therefore, a robust, well-written project specification should consider the standard galvanising process and procedure but, in addition, set its own quality control and quality assurance requirements. The following limits should be considered important:

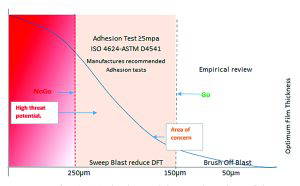

• Upper Galvanising Limit: The galvanising thickness must be strictly controlled. Any measurements exceeding 250 µm should trigger a formal integrity assessment. Sections with thicknesses greater than 250-400 µm should be quarantined until additional quality control testing can give assurance of acceptability. This includes but is not limited to. Adhesion testing using both internationally recognised standards and EPFP manufacturers’ recommended procedures.

• Mill Test Certificates: Engineers and specifiers should always review the steel’s Mill Test Certificate (MTC) at the design stage. An MTC (specifically a Type 3.1 certificate as per ISO 10474) provides a detailed chemical breakdown. If the silicon and phosphorus levels are high, excessive galvanising growth could be considered predictable, and the required additional inspection protocols can then be implemented by the engineer early at the galvaniser’s facility.

4.Defects Which Could Impair Performance

Defects within the galvanising layer that may create points of failure.

• Ash and Dross Inclusions: Ash (zinc oxide from the zinc bath surface) and dross (iron-zinc particles from the bath bottom) can become entrapped in the coating. These inclusions can be poorly bonded, creating an area of instant non-adhesion for the primer and EPFP [3].

5.Process Factors which Could Impair Performance

Properties at the surface of the galvanising layer that may create immediate points of failure.

• Passivation and Quenching: Post-treatment of galvanised surfaces with chromates or water quenching is common. Water quenching creates a thin, weak layer of zinc oxides and hydroxides on the surface. Chromate treatments are often used for aesthetics.This layer is completely unsuitable for coating adhesion and should be prohibited in the project specification. Any steel that has been water-quenched should be rejected before an EPFP application.

• Use of Cold Spray Repair Compounds: Where surface defects are observed by the galvaniser, cold spray repair compounds may be used to improve the aesthetic appearance of the galvanising.

Note. These repair compounds are not compatible with EPFP systems and may lead to coating system delamination. Any items where cold spray repair compounds have been used should be rejected prior to EPFP system application.

6.High Film Builds: A Closer Look at the Implications

When a thick-film material like EPFP is applied over a cohesively weak galvanised layer, several critical issues could materialise.

1. Adhesion Failure: The primer for the EPFP system cannot achieve a proper bond to a galvanised surface which is contaminated with weak oxide layers or has incompatible treatments applied. The failure point is within the incompatible treatment in the case of cold spray repair compounds or between the primer and the galvanised steel.

2. Internal Stress: The EPFP can induce stress during cure, and a brittle or weak, over-thick layer may crack or delaminate.

7. Remedial Actions: No Half Measures

When non-conformances are found, the remedial actions need to be appropriate to the EPFP system application. The goal is not to “repair” the galvanising in the traditional sense but to create a sound substrate for the EPFP.

1. Quarantined: For issues like water quenching or thickness exceeding 250 µm to 400 µm, the section should be quarantined. Until quality assurance can be demonstrated.

2. Thorough blasting with appropriate media: For sections with excessive thickness (250 µm – 400 µm) or surface defects like ash, the only acceptable method of repair is to aggressively abrasive blast. The goal of a “sweep blast” is not merely to create a profile; it is to remove the defective and friable outer layers of the galvanising until a sound adherent zinc layer is exposed. If this means blasting through to harder alloy layers in localised areas, then the justification can be presented: “Lifetime expectation is met by the application of the EPFP system.” However, this must be brought to the client’s attention as a technical or engineering query, as it fundamentally changes the specification requirement.

3. Stop Inadequate Repairs: Standard galvanising repair methods, such as cold spray repair compounds detailed in standards like ASTM A780, or the use of zinc-based solders (“zinc sticks”), should not be accepted for surfaces receiving EPFP. These repairs do not possess the cohesive strength or compatibility with the EPFP system and could create a point of failure.

All galvanised steel specified for EPFP application should always be sweep blasted to remove surface contaminants and any weak oxide layer, providing an angular profile of 50-75 µm for the EPFP system to anchor against. This should be stated clearly in the specification.

8. Conclusion: A Call for Best Practice

The industry must shift its mindset. Applying EPFP over hot-dip galvanising introduces significant, unnecessary risk to a facility’s most critical safety infrastructure. The default specification should always be EPFP applied directly to appropriately primed steel prepared to the EPFP manufacturer’s requirements.

When galvanising is unavoidable, it must not be treated as a finished product but as a substrate in need of quality control and further preparation for the EPFP system.

To achieve a safe and reliable outcome, the following actions should be considered essential.

• Early Intervention: Review mill test certificates at the project’s outset to identify reactive steels and plan for heightened inspection.

• Specify Correctly: Write a detailed coating specification that explicitly prohibits water quenching and surface treatments and defines strict lower and upper thickness limits for the galvanising coating.

• Mandatory Surface Preparation: Mandate that all galvanised surfaces receive an aggressive sweep blast to remove weak layers and create a suitable surface profile before priming.

• Consult the Experts: Engage the EPFP manufacturer at the design stage to assist with specifications and inspection test plans (ITPs).

By prioritising the integrity of the substrate, we can ensure that these vital safety systems perform as designed, protecting assets, the environment, and, most importantly, lives.

References

1. https://www.glorysteelwork.com/2024/05/07/causes-and-control-methods-of-hot-dip-galvanizing-surface defects/#:~:text=If%20there%20are%20more%20active,layer%20grow%20rapidly%20and%20push.

2. Kestler., C. E. (n.d.). The Galvalume Sheet Manufacturing Process. In C. E. Kestler., The Galvalume Sheet Manufacturing Process.

3. https://steelprogroup.com/galvanized-steel/finish/defects-and-treatment/#:~:text=Ash%20staining%20is%20caused%20by,dipping%2C%20leaving%20a%20grayish%20stain.