Meet The Authors

Introduction

The term ‘ageing factor’ (sometimes referred to as ‘ageing constant’) for galvanic Anodes, was first coined by Sergi et al in ‘Monitoring results of galvanic anodes in steel reinforced concrete over 20 years’ in Construction and Building Materials, 2020 [1]. The principle behind this idea is that discrete measurements of galvanic current data from precast anode systems, when plotted on a logarithmic graph, could be fitted with a straight line. Therefore, they claim that their anodes exhibit a ‘half-life’ model with the current trending to zero, halving over set time intervals, the ‘ageing factor’. They further claim that when the anodic current density falls below a threshold, the anodes no longer adequately protect the steel reinforcement.

Modelling – Apparent Discrepancies

The first site analysed by Sergi et al. was a bridge in Leicester; current was measured. approximately 26 times for 12 individual patch-anodes from a single patch over 20 years. The initial description of the anodic current describes three distinct stages of relatively stable current output, each below the prior level: 0-6 years, 7-14 years and 15-20 years. This was described, at least in part, due to a drop in pH of the pore solution of the electrolyte. A half-life ageing constant of approximately 7 years over which the current would half was then generated by the plotting of the current readings on a logarithmic scale and a straight line being fit to the data [1]. The reason for the choice of a logarithmic scale is not fully explained, with decreases in surface area and depletion of lithium hydroxide being cited.

This concept was furthered in the next year in the Journal of Building Engineering (June 2021) [3], at the Corrosion Conference (November 2021) [4], Structural Faults and Repair Conference (2022), an ICRI webinar, ’Design Considerations for Galvanic Anodes’ (December 2022) [5], in the book Life-Cycle of Structures and Infrastructure Systems [6], and 3rd Conference & Expo Genoa (2024) [7]. Throughout these publications, ‘ageing factors’ were published for approximately 12 elements using precast Vector Corrosion Technologies (VCT) anodes and their precast precursors, and included both site and laboratory data. Of particular note was the ICRI webinar and the AMPP Italy Corrosion Conference white paper, where the half-life style ‘ageing-factor’ hypothesis was applied to non-precast anodes manufactured by other companies, including Concrete Preservation Technologies (CPT) and an ‘ageing factor’ was published for CPT’s hybrid anode, one that is initially powered externally before being wired galvanically, the DuoGuardTM anode system [5,7]. The predicted ‘ageing constant’ published for these anodes was 2.9 years, and was compared unfavourably to the 11 year ‘ageing factor’ for their own products.

There were however, some significant changes made to use of this empirical model. Rather than being a model for some precast patch anodes manufactured by a single company and their precursor anodes the hypothesis was now being applied to anode arrays cast with a different geometry, embedded in a different cementitious material, located in the host concrete rather than a patch, and very importantly not activated using the same chemistry that was cited as a major cause of the exponential decay in the original paper [1]. DuoGuardTM is activated chemically in such a way that the activator is not depleted but recycled, continually drawn back to the anode. Therefore, the theoretical underpinnings cited by the authors do not appear to hold for these anodes. This has led to the need for a closer look at this model and whether it can tell us anything about the behaviour of these anode systems or whether the model can reliably predict the behaviour of CPT anodes.

In order to understand this model, it is important to first explore the stated and hidden axioms behind the hypothesis and how these lead Sergi, Whitmore and others to interpret their data in such a way. In this section, we will place to one side the fact that there is no stated theoretical underpinning to the choice of a logarithmic scale and allow for the strength of the predicted current data to judge

its veracity.

Half-Life Theory Axiom – There is A Set, Minimum Current Threshold For the Protection of Steel In Concrete

The corrosion risk of steel is due to its environment. This should be a relatively uncontroversial statement, as it is known that steel in fresh concrete is passive and requires no cathodic protection, and steel in carbonated concrete has a lower corrosion rate on average than steel in chloride-rich environments [8]. Furthermore, corrosion rates can vary due to the exposure to moisture, availability of oxygen and be changed by coatings applied to the steel. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the amount of protection steel in concrete requires for protection is a product of its environment.

Although the authors do acknowledge the importance of chloride in the amount of current needed to protect steel in concrete [7], they ignore many of the other factors. This inherent complexity is why it is often much easier to measure changes in the steel due to protection rather than purely the current output of the system. Such measurements are common with impressed current cathodic protection (ICCP) systems that use ISO 12696:2021 [9], which gives steel potentials in the immune region and polarisation held in the steel. originating from Mixed Potential Theory [10,11], as criteria for protection. Within galvanic cathodic protection (GCP), it is common to track the depolarised steel potentials [12] to measure changes in corrosion risk, polarisation [13] and corrosion rates [14,15]. These measure the effect of the anodes on the steel rather than the output alone to determine the level of protection achieved.

Comparison of Anode Systems

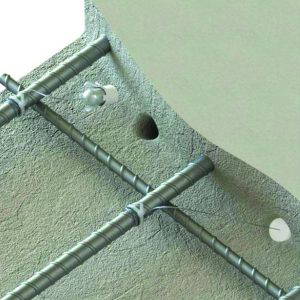

This is further complicated by the fact that some anode systems are installed in different ways, leading to varied current spread. It matters very little how much current an anode produces if it is not reaching the at-risk steel it is installed to protect. To explain this concept more clearly, two anode systems for patch repair will be compared: a precast anode designed to be tied onto the reinforcement in a patch and a patch anode that is installed into a putty in the periphery of the patch, away from a single steel rebar. Below CPTs precast anode RebaGuardTM and drilled anodes PatchGuardTM can be seen. RebaGuardTM is similar to the anodes installed in many of the author’s works.

The steel being protected by patch anodes is the steel outside of the patch, as the steel in the patch is in fresh, alkaline, contaminant-free concrete. The precast anodes are tied to the steel within the patch. It is not difficult to see that it is likely that a large portion of the current will take the easiest path between the zinc and the steel, to the reinforcement onto which it is tied. The current that does exit the patch must avoid taking the easiest path, passing through the interface between the patch and the host concrete, which will have a resistance and spread to the steel outside of the patch which is at some distance from the anodes. These anodes can and do work, but it is unlikely that all the current they produce is available to the steel they are protecting.

The PatchGuardTM anode is installed into the periphery of the patch, in the host concrete into a conductive putty, much closer to the steel it is designed to protect. Unlike the precast anodes, it is not tied to a single reinforcement, and the current will therefore more easily spread to the at-risk reinforcement. Furthermore, due to the increased resistivity of most patch materials and the resistive interface of the patch making current flow into the patch more difficult, it will favour passing current to the steel outside the patch rather than within the patch. It is therefore logical to think that the current from this PatchGuardTM anode will protect the rebar much more efficiently than the precast anode. Having the same current requirement for each of these anodes is illogical.

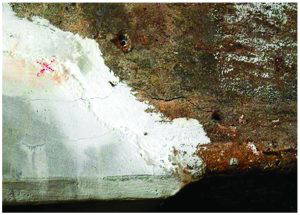

The validity of their threshold may be tested using the author’s data. The first work published in this series was the 20-year data from a ‘bridge in Leicester’ [1]. This site is a site which staff at CPT is quite familiar, and many senior members of staff were present at the installation of these anodes. Though the paper claims that after 20 years that the anodes are reaching the end of their life, with the current output dropping under their threshold for protection at approximately 14.5 years. In a statement to the Cathodic Protection Association (CPA) from March 2023 by CPT [16], it was shown that in 2015, ten years after the installation of the anodes, there was cracking in the element following the line of the reinforcement extending from the repairs. This is not a measure of success in a galvanic anode system and shows a flaw in their current threshold.

Potential Measurement Error – Taking Current Data From A Responsive System

One of the most important concepts with galvanic anodes is their responsive behaviour [17,18]. The driving voltage, as long as the anodes are activated, is due to the galvanic series and therefore can be approximated as constant; the current delivered to the steel is therefore largely dependent on the resistivity of the electrolyte in the circuit, the concrete. So, when the concrete is wet, full of ions, warm, etc, the circuit has a lower resistance and the cell between the zinc and the steel produces a higher current. This is a part of the draw of these anode systems as they give a level of protection which changes with the corrosion risk of the environment.

One of the issues that comes with this fluctuation in current is that when the anode currents are measured infrequently without other corresponding data, such as the weather. Steel polarisation or natural steel potentials – the data can be misleading. Currents taken on wet and warm days may be much larger than those taken on dry and cool days, which can make seeing trends in current output difficult, unless Adequate data is collected.

Furthermore, anodes installed into wet patches, or into slow-curing putties may have initial currents which are atypical due to the moisture surrounding the anode, decreasing the resistance between the zinc and the steel. In CPT’s anode systems, the putty may take many years to cure, a design feature to initially provide a larger current to aid in the passivation of the steel due to the reduction reactions at the steel surface producing hydroxide ions.

This ageing constant generated for CPT DuoGuard anodes was created from a few data points using anodic current data from

only the first nine years of the galvanic protection [7]. This was during the period when the putty was curing. This may have led

to some inaccuracies in predicting the long-term behaviour of these anodes.

Whiteadder Bridge – Duoguard Hybrid

Anode System CASE Study

The data used by Sergi et al to calculate the ageing factor for DuoGuardTM anodes was taken from data published from Whiteadder Bridge in the UK [17].Here, two zones of anodes

were installed within a proprietary putty in regularly spaced,

drilled holes, and wired together to form arrays which protect the upper and lower portions of the structural element supporting the span of the bridge over a river. The anodes were installed to counteract the corrosion issues caused by de-icing salts and moisture ingress, including tidal flooding of the river.

The anodes were initially powered until at least 50kC of charge had been passed for every square meter of steel surface area to realkalise the steel environment, utilising the zinc’s ability to pass much higher currents than MMO titanium anodes when powered, and then connected directly to the steel via a junction box. Reference electrodes were installed in the zones, and the current output of the anodes alongside the reference potentials were measured by a data logger installed in an enclosure. This gives a constant stream of data, far in excess of those sites of similar ages used in the work by Sergi and Whitmore.

The element has been protected for 18.5 years now without the need for any maintenance beyond the replacement of SIM cards in the enclosure which transmit the data wirelessly to our office, and has been monitored with over 100,000 data points collected over the first 17.5 years of protection in each zone and over 1,000,000 data points collected in sum. The data used for the predicted 2.9-year ageing factor found in the AMPP Italy white paper [7] was taken from the first 9 years of data [17], which was not the most recent publicly available data set at the time [18] and appears to include only a small number of data points. It is unclear how these data points were selected. Due to the initial charging of the anodes, the authors claim that it would be expected that such anodes would likely have a decreased life due to having to pass a large amount of current early in their design life [7].

Although this model is now used in specifications and design documents worldwide, this will be the first predictive test of their empirical model and, importantly, a test of whether this model can be applied to anodes other than their own, for which they likely have a greater abundance of data. The aim of the following section is to analyse the predictive power of this model using data from the CPT site used in their analysis using the most recent data collected which presumably they had little access to.

Site Data – Responsive Behaviour

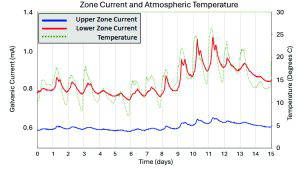

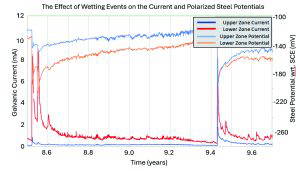

Below are the current and the polarised steel potentials for the lower zone of anodes installed on Whiteadder Bridge above, the same data used in the author’s work [7,17], but now with an additional 8 years of data. The red line is the galvanic current data showing the characteristic responsive behaviour with currents rising and falling in yearly cycles due to temperature changes and peaking during periods of increased moisture due to rainfall or flooding. This supports the theory that current is being driven in these anodes due to changes in resistance in the concrete electrolyte. The blue line is the polarised steel potential. When the current increases, we see a corresponding peak in the steel potential as the current generates a polarisation in the steel. Polarisation is a sign of steel passivity, with more passive steel polarising more easily than corroding steel. A green line has been added to show that over time the steel potentials are trending less negative, an indication of increased steel passivity.

The first few years of the data do show an increased current output from the anodes. As was previously stated, this is likely due to the putty into which the anodes were installed curing. After this period, the current appears to become more stable and respond to changes in resistivity from a relatively stable baseline. Taking a closer look at the data from around 9 years after installation, we can see the current from both zones increases due to fluctuations in temperature during the day as well as throughout the year. This response to corrosion risk with increased protection is one of the hallmarks of a naturally smart corrosion management system that is driven by electrochemistry.

After flooding and rainfall, we can see that not only does the current increase due to the moisture ingress, but it also falls slowly as the moisture evaporates, leading to increased protection during the entire period of increased risk. Furthermore, some of the peaks in current seen during periods of increased moisture are larger than

the initial anode current, indicating that the current output is not being primarily driven by a build up of corrosion products or a depletion in activator for these systems but a reaction to the environment and the corrosion risk.

Testing he Predictive Power of The Half-Life ‘Ageing Factor’

In order to test the predictive power of the model, we must choose a null hypothesis against which it will be compared. The simplest null hypothesis would be that the median current the system was producing between 8 and 9 years, the last year of the data set utilised by the authors, stays constant. This appears to be a fair null hypothesis to test their predicted values against, as one predicts a decrease and the other predicts no decrease in current.

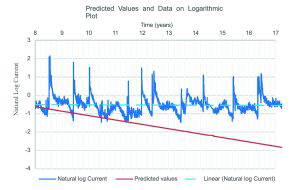

The authors published a half-life ‘ageing factor’ of 2.9 years, where the current halves every 2.9 year period. Here we have plotted the predicted values for each hypothesis against the data collected from the site during the period from year 8 to year 17, approximately 3 ageing factors or an expectation that the current, if the model is correct, will fall by more than 87.5%. A log current graph was chosen to transcribe the half-life model data into a straight line in a similar fashion to that employed by Sergi in

his work.

As can clearly be seen, the values predicted by the ‘ageing factor’ model (red) diverge from those measured on site over time, whereas the constant current model fits the data much more closely. This becomes evident when the mean squared error (MSE) of each predicted data set is measured; with the half-life hypothesis having an MSE of 0.237 mA2 and the MSE of a simple constant value

model being 0.0135 mA2, an order of magnitude smaller.

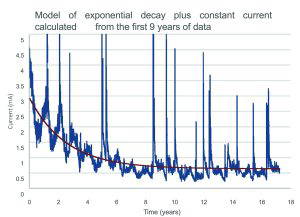

The error is likely due to a misunderstanding of how these anodes will behave differently over time due to their activation chemistry and presuming that the same methodology should be employed without testing other hypotheses, leading to the authors choosing to fit the same exponential decay that fit their own data. A simple change in their methodology to presume an exponential decay overlaying a more stable pattern can lead to a much better fit in the data and a lower MSE over the previously available data.

Below is an empirical model presuming a decay plus a constant current calculated using the first 9 years of data only. It should be noted that this is not a lifetime predictive model for these anodes, which will depend on many factors, as the anodes will not continue protecting the steel indefinitely and it is expected that when the volume of the anodes reduces beyond a threshold the ratio of zinc to steel surface areas will be insufficient to pass the same current. This fact in included in the design calculations of these anode systems. This is also not an endorsement of current being used as a benchmark for anode performance. However, as around 7% of the anodes on this site have currently been consumed, in the lifetime provided for this system it is unlikely to reach this threshold and this basic model may suffice, depending on environmental conditions. Therefore, over this limited time period, a relatively stable current may be used as changes in surface areas are relatively slow due to the anode geometry chosen by CPT and the activator should continue to keep the zinc active. An initial period of higher current due to the resistivity drop from the curing of the putty is also included in this limited model.

We believe that much of the error in the predicted value of the ageing term is due to the presumption that the overall behaviour would be similar. However, the difference in the activators used to keep the anodes active may lead to differing behaviour giving precast anodes an exponential decay of current to zero. This depletion in their activator, may lead to the amount of protection being in a large part dependent not on the amount of zinc but rather on the amount of activator utilised. Activators such as lithium hydroxide are consumed, may be leached away from the anodes, and carbonate after manufacture. Anodes activated in similar ways to PatchGuardTM and DuoGuardTM are likely to age very differently, as the availability of activator will not deplete in the same fashion and are therefore unlikely to show the same ageing characteristics. This can be seen clearly by calculating their hypothetical ageing constant using the data from years 8-17 using the same method as Sergi et al. Here we calculate the ageing constant over which the current is halved to be over 36,000 years. This is plainly absurd, as the zinc will be completely depleted after around 100-250 years. The underlying ageing of CPT anodes is therefore very unlikely to be exponential in nature.

Conclusions

It is clear from this data that the major factor driving the current output of CPT’s discrete anodes, is changes in the resistivity of the environment. After 17 years, the current was still responding strongly to changes in moisture, producing currents in excess of the median galvanic current from the first year of installation when moisture ingress reduces the resistivity of the environment. Precast anodes, such as the type used in the creation of the half-life model, may also be limited by a second factor, the depletion of their activator. This is concerning as these anode types are very popular worldwide and are often sold based on a mass of zinc, when, without sufficient activator, that mass of zinc will not be fully utilised. With lithium hydroxide as an activator, the mass of the activator would likely need to be much greater than the mass of zinc. It is likely, therefore, that only a portion of these anodes will be sufficiently activated before the current declines substantially.

Due to the depletion of activator, some form of ageing term may well apply to VCT style products as stated by their authors. However, due to this hypothesis failing to accurately predict the behaviour of other anode systems, it should be avoided in all specification documents as it may be unique to a certain set of products. It is important to ensure that clients are getting the same level of protection from anodes sold as equivalents in the market.

References

[1] G. Sergi, G. Seneviratne, D. Simpson, Monitoring results of galvanic anodes in steel reinforced concrete over 20 years, Construction and Building Materials, Volume 269, 2021, 121309, ISSN 0950- 618, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121309.

[2] G. Sergi, Galvanic Corrosion Control of Reinforced Concrete: Lessons Learnt from 20 Years of Site Trials, ICorr presentation, Aberdeen, 30/03/2021, https://www.icorr.org/wp- content/uploads/2021/06/2021-03-30-ICorr-Aberdeen-Event-ICorr-Aberdeen-Presentation-30-03-21- Dr-George-Sergi-Vector-Corrosion.pdf 2021.

[3] G. Sergi, G. Seneviratne, D. Simpson, Monitoring results of galvanic anodes in steel reinforced concrete over 20 years, Construction & Building Materials, 269, 121309 2021.

[4] D. Whitmore, G. Sergi, Long-term monitoring provides data required to predict performance and perform intelligent design of galvanic corrosion control systems for reinforced concrete structures, Corrosion 2021, AMPP, Paper No. 16792, 2021.

[5] D. Whitmore, Design Considerations for Galvanic Anodes, ICRI webinar, December 2022.

6] G. Sergi, Life extension of existing steel reinforced structures by simple cathodic protection techniques for sustainable durability, Life-Cycle of Structures and Infrastructure Systems – Biondini & Frangopol (Eds), ISBN 978-1-003-32302-0 2023.

[7] G. Sergi, P. McCloskey, D. Simpson, Long-term performance of galvanic anodes for steel reinforced concrete, 3rd Conference & Expo Genoa 2024, AMPP Italy,https://www.vector- corrosion.com/assets/page_renderer/Sergi_George-Extended_Abstract.pdf, 2024.

[8] L. Bertolini, B. Elsener, P. Pedeferri, & R. Polder, Corrosion of Steel in Concrete: Prevention,Diagnosis, Repair. Corrosion of Steel in Concrete: Prevention, Diagnosis, Repair, 1–392. 2005 https://doi.org/10.1002/3527603379.

[9] ISO BS EN 12696:2022.

[10] G. K. Glass, A. M. Hassanein, N. R. Buenfeld, Monitoring the passivation of steel in concrete induced by cathodic protection, Corrosion Science, Vol. 39, No. 8, pp. 1451-1458, 1997.

[11] C. Stone, G. K. Glass, Assessment Criteria For The Electrochemical Protection Of Steel, Australasian Corrosion Association Conference, Cairns, November 2024.

[12] Standard Test Method for Corrosion Potentials of Uncoated Reinforcing Steel in Concrete, ASTM C876 22b, October 2022[11] National Highways 5700 Series.

[13] C. Christodoulou, C Goodier, S. A. Austin. Site performance of galvanic anodes in concrete repairs. Concrete Solutions-Proceedings of Concrete Solutions, 5th International Conference on Concrete Repair 2014 Aug 18 (pp. 167-172). 2014.

[14] Corrosion of steel in concrete: investigation and assessment, BRE Digest 444, 2000, ISBN 860813615.

[15] Electrochemical tests for reinforcement corrosion, Concrete Society Technical Report 60, 2024.

[16] G. K. Glass, Statement to the Cathodic Protection Association, SCA technical Meeting, March2023.

[17] D. Bewley, High-power, low-maintenance, hybrid corrosion protection, Bridge construction and repair, Concrete, Oct 2016, pp. 25-27 2016.

[18] D. Bewley, C. Stone, Long-term monitoring of innovative corrosion control system yields fascinating results, Concrete, Volume 57, Issue 5 June 2023.

Editor’s Note

This Journal provides a platform to all to present their investigations and research. It is not the intention to endorse particular products and readers must satisfy themselves in regard to their applicability and their particular needs.