]

Introduction

Corrosion poses significant challenges to the structural durability, longevity, and integrity of marine infrastructure and shipping worldwide due to the increasing costs of maintenance, spare parts, component replacements, and the risk of catastrophic structural failures [1]. The corrosion processes affecting marine structures and vessels are influenced by operational conditions, material properties, and environmental factors, including the corrosive nature of seawater driven by salinity, pH, temperature, electrolyte composition, and oxygen concentration [2]. Therefore, it is essential to regularly or periodically monitor and inspect the condition of metallic components in marine structures and ships. Traditional methods—such as predictive models, electrochemical tests, and visual inspections—are often inadequate for highly complex structures, large-scale hulls, labour-intensive and hazardous environments, and early-stage corrosion detection. These limitations highlight the need for more efficient, reliable, accurate, and advanced technologies for corrosion survey, inspection, and maintenance.

In recent years, Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning and deep learning, has emerged as a transformative approach in corrosion research. Although AI does not replace the requirement for peer review and engineering competency, AI does enable the analysis of vast datasets, the identification of hidden patterns, and the generation of precise predictions regarding corrosion behaviour under varying conditions [3]. Techniques such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Vision Transformers, Random Forests, and others have been applied to corrosion surveying [4], inspection [5], and maintenance [6], as documented in current literature. These AI methods are increasingly being integrated with traditional techniques to enhance and improve outcomes. Predictive maintenance, in particular, is an essential AI-driven strategy that aims to determine the optimal timing for maintenance activities, especially concerning structural integrity and corrosion in marine environments. Its main advantages include cost reduction, increased safety (automation reduces human intervention), minimisation of unplanned downtime, and support for environmental sustainability [7]. However, the predictive maintenance framework for corrosion monitoring remains underdeveloped and sparsely reported in the literature [8]. Notably, there is a lack of a comprehensive framework addressing sensor systems, data storage and management, predictive modelling and analytics, and the deployment of Remote Inspection Techniques (RIT). Hence, this research aims to propose a predictive maintenance framework for corrosion monitoring using AI. The main contributions of this study are:

1. A predictive maintenance framework for AI-based corrosion monitoring that includes several key components working together to anticipate structural failures and optimise the timing of corrosion maintenance on marine structures and ships.

2. RIT regulations, particularly for drone or Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV), unmanned robotic arm, and crawler/climber, that standardize and regulate the operation of RIT at sea in compliance with International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) recommendations and International Maritime Organization (IMO) standards when deployed on ships and vessels for survey, inspection, classification, and maintenance.

3. The developed framework aims to standardise the process and organisation of AI-based predictive maintenance for corrosion monitoring, making it easier to regulate globally, especially for marine structures

and ships.

The Framework

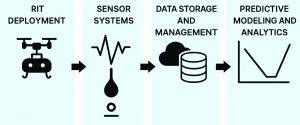

The framework is developed with four key components which are RIT deployment, sensor systems, data storage and management, and predictive modeling and analytics.

• Component 1 – RIT deployment, focuses on establishing a set of regulations and operational procedures for RIT tools and equipment, including drone, ROV, USV, crawler, climber, and unmanned robotic arms, particularly for use on ships.

• Component 2 – Sensor systems which can either be installed directly on marine structures or integrated with RIT tools to collect various types of data, including image data in the infrared or visible spectrum using optical sensors [9].

• Component 3 – Data storage and management. The large volume of data collected from sensors necessitates the use of cloud-based big data storage systems for efficient management and analysis. Reliable communication and data transfer between the sensors and the cloud are crucial to enable real-time analysis with high accuracy [10]. Multiple communication protocols must be established to ensure data integrity in uncontrolled and harsh marine environments.

• Component 4 – Predictive modeling and analytics. Predictive models are developed using historical and real-time data related to corrosion parameters on marine structures and ships [11]. The proposed framework is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

RIT Deployment

The first component in the framework is RIT deployment. RIT refers to methods used to examine parts of marine or ship structures without requiring direct physical access [12]. The maritime industry is increasingly adopting RIT, as these techniques offer greater efficiency, higher flexibility, and improved reliability in the day-to-day operations of survey and inspection, without compromising the quality of the results [13]. Various RIT tools or equipment can be used for marine structures and ships, depending on the shapes and surfaces involved. Drones are particularly flexible for surveys and inspections, as they can access open spaces, hard-to-reach areas, elevated locations, hazardous zones, and confined spaces [14]. Meanwhile, ROVs are used for underwater inspections where other RIT tools cannot operate [15]. Since visibility underwater is often moderate or poor, high-quality optical sensors are required for effective inspection. USVs are used to inspect structures near the water surface [16]. Crawlers or climbers are suited for hull inspection and maintenance while the ship is sailing and far from the coast [17]. Unmanned robotic arms can also be utilised to access parts of marine and ship structures that are otherwise difficult for humans to reach [18]. Following the surveying and inspection processes conducted using RIT tools, maintenance activities can be planned and executed accordingly. These tools scan marine structures and ship compartments systematically, and predictive maintenance systems then analise the data to support real-time maintenance decision-making and implementation. The ship

affected with corrosion is illustrated in Figure 2.

Moreover, all RIT tools deployed on ships must comply with the recommendations and standards set by IACS and IMO to ensure the safety and well-being of workers and assets. IACS Recommendation 42 (Guidelines for Use of Remote Inspection Techniques for Surveys) outlines the controlled use of RIT to enhance survey processes, emphasising that these techniques are supplementary and must be conducted under strict guidelines to ensure safety and regulatory compliance. According to IACS Recommendation 42, all RIT operations must be witnessed by an attending surveyor to validate the inspection. RIT tools must be properly calibrated and tested before use, and the operators conducting the inspections must be qualified. An inspection plan detailing the RIT methods, equipment, and procedures must be submitted in advance for review and approval. Regarding inspection conditions, the structures must be sufficiently clean to allow meaningful examination, and visibility must be adequate for accurate assessment. For data handling, effective two-way communication between the surveyor and the RIT operator is essential. The surveyor must be satisfied with the quality of the data presentation, including visual representations.

Despite the advantages of RIT, its use for close-up surveys under specific conditions in ship inspections remains restricted or limited due to concerns related to the health, safety, and accuracy of RIT tools and associated assets. If such conditions are detected, traditional close-up surveys may be required. To address this, IACS has proposed amendments to the 2011 ESP Code to incorporate more technical procedures for RIT, including the formal definition of RIT within the code, permission for its use in close-up surveys, and the establishment of specific requirements for RIT applications. Furthermore, it is important to differentiate between RIT and remote surveys in the context of the code. RIT involves the physical attendance of a surveyor using remote tools to inspect areas that are difficult to access, while remote surveys are conducted without the physical presence of a surveyor, typically relying on electronically transmitted data. It is essential to note that the use of RIT is restricted in situations where conditions of class for repairs are imposed, or when there is a record or indication of abnormal deterioration or damage. Additionally, the proposed amendment supports the use of RIT to assist surveyors in their inspection tasks without compromising the accuracy or integrity of the surveys. When RIT is employed for close-up surveys, temporary access means must be provided for thickness measurements unless the RIT system is also capable of performing those measurements. In this context, ultrasonic thickness gauges can be installed on RIT equipment to allow simultaneous data collection. The amendment to the 2011 ESP Code has the potential to enable safer surveys, reduce inspection errors, and lower maintenance costs, particularly in corrosion-related cases. The details of 2011 ESP Code amendment can be referred here [19]. Figures 3 show the RIT implementation using drone and climber for ship survey and inspection.

Sensor Systems

The second component in the framework is the sensor systems. Vibration, temperature, humidity, pressure, acoustic, optical, and ultrasonic thickness measurement sensors can be used to survey marine and ship structures. These sensors must be durable enough to operate in harsh marine environments. They can either be equipped on RIT tools or directly installed on the structures. These sensors continuously monitor the health of structures and equipment to detect early signs of degradation. According to the amendment to the 2011 ESP Code, RIT must provide the extent and quality of information normally obtained from a close-up survey. This means that the sensor systems must be reliable and deliver accurate data to assist the surveyor. The data collected from the sensors will serve as input for predictive modeling, and the output from the predictive models will be presented to the surveyor. The surveyor must be satisfied with the method of data presentation, including pictorial representations of corroded areas on the structures, in order to verify the results of predictive maintenance. For network communication between sensors and the cloud, options include Wi-Fi, cellular (4G/5G), Long Range Wide Area Network (LoRaWAN), Ethernet, or RS-485. Edge devices or computing platforms such as Raspberry Pi, Arduino, ESP32, and others can be used to convert, filter, compress, and transmit sensor data to the cloud via these communication networks. Common communication protocols include MQTT and HTTP/HTTPS, which are widely used for transmitting messages and data between servers and clients.

Data Storage and Management

Once the data from sensors, transmitted via edge devices, reaches the internet through a gateway or direct connection, it is sent to a cloud platform such as AWS IoT Core, Azure IoT Hub, Google Cloud IoT Core, MATLAB ThingSpeak, or other cloud services. Those cloud services are tailored for IoT applications. The types of data may include time-series data, images, and logs. In the cloud, the transmitted data is managed based on the surveyors’ tasks. It is pre-processed to remove noise, handle missing values or outliers, and apply appropriate data labeling. All data is securely stored, and data analytics can be performed online using either existing AI models or models developed by the surveyors. The data is processed accordingly and then stored for future use. The cloud facilitates real-time data processing from the sensors and supports long-term trend analysis, which is essential in the context of corrosion monitoring. Effective data management ensures that historical corrosion trends are captured, and the data can be accessed or visualised on demand.

Predictive Modeling and Analytics

This component involves turning raw sensor data into actionable insights about when and where corrosion will occur, how fast it is progressing, and when intervention is needed. AI-based predictive modeling can identify and quantify corroded regions, as well as forecast corrosion rates with high accuracy. Machine learning and statistical models are applied to predict future failures or RUL, detect the early onset of corrosion through anomalies, and trigger maintenance alerts before failures occur.

These predictive models can include decision trees, neural networks, support vector machines, or other AI-based methods. For corrosion rate estimation, data-driven methods such as machine learning regression can be used. For RUL estimation, models like random forests or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks may be applied. For anomaly detection, techniques such as k-means clustering or autoencoders can be utilized. For image analysis, vision transformers or CNNs are suitable. For corrosion risk scoring, support vector machines or Naive Bayes classifiers can be employed. Common tools for AI model development include TensorFlow, Google Colab, MATLAB, XGBoost, OpenCV, PyTorch, and Keras. Despite the methods mentioned above, there are no strict restrictions on which AI models can be used for each application or case. Once a potential failure is predicted by the models, decision-making tools assist in determining the optimal maintenance actions, taking into account factors such as cost, downtime, and risk. Predictive outputs should be integrated into enterprise systems (e.g., CMMS, ERP) to automatically trigger work orders or adjust operations. However, in the context of ship surveys, IACS Regulation 42 and the 2011 ESP Code amendment mandate that RIT support surveyors in their close-up survey activities without impairing the quality of the surveys. At the same time, surveyors must verify the results produced by RIT and predictive maintenance. This means the output from predictive maintenance will assist surveyors in making informed decisions regarding the structural integrity of ship structures.

Conclusions

Our global maritime industry is increasingly adopting RIT for marine structures and ship applications. The integration of predictive maintenance with RIT for surveys, inspections, and maintenance enhances efficiency and accuracy without compromising the results of conventional surveys. The proposed new framework provides real-time condition monitoring in place of periodic inspections, early warnings of hidden damage (such as corrosion under insulation), optimized inspection schedules (condition-based rather than time-based), better resource allocation, and non-invasive detection methods. These improvements can reduce the risk of sudden leaks, failures, or environmental incidents, while also enabling data-driven decisions with quantified confidence. Additionally, the proposed framework contributes to standardising the processes and organisation of AI-based predictive maintenance for corrosion monitoring, particularly in the context of surveying, inspection, and maintenance of marine and ship structures. It is evident that the prediction output from the framework will assist surveyors in making informed decisions regarding the structural integrity of marine and ship structures, especially in the context of corrosion. In the future and with input from competent engineering resources, AI models can be further fine-tuned to improve the effectiveness of predictive maintenance outputs in supporting surveyors’ decision-making.

References

[1] M M H Imran et al., A Critical Analysis of Machine Learning in Ship, Offshore, And Oil and Gas Corrosion Research, Part I: Corrosion Detection and Classification, Ocean Engineering 313 (2024). 119600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.119600

[2] I M Chohan et al., Effect of Seawater Salinity, Ph, And Temperature on External Corrosion Behavior and Microhardness of Offshore Oil and Gas Pipeline: RSM Modelling and Optimization, Scientific Reports 14(1) (2024). 16543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67463-2

[3] W Liang et al., Advances, Challenges and Opportunities in Creating Data for Trustworthy AI, Nature Machine Intelligence 4(8) (2022). 669-677. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00516-1

[4] O A Oyedeji, S. Khan, J A Erkoyuncu, Application of CNN for Multiple Phase Corrosion Identification and Region Detection, Applied Soft Computing 164 (2024). 112008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112008

[5] A Subedi et al., CorFormer: A Hybrid Transformer-CNN Architecture for Corrosion Segmentation on Metallic Surfaces, Machine Vision and Applications 36(2) (2025). 45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00138-025-01663-2

[6] M Gavryushina et al., A Marshakov, Y. Panchenko, Application of the Random Forest Algorithm to Predict The Corrosion Losses of Carbon Steel Over the First Year of Exposure in Various Regions of The World, Corrosion Engineering, Science and Technology 58(3) (2023). 205-213. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478422X.2022.2161336

[7] M M H Imran et al., Effective Periodic Noise Reduction for Ship Corrosion Image, Journal of Advanced Research Design 129(1) (2025). 130-147. https://doi.org/10.37934/ard.129.1.130147

[8] M M H Imran et al., Advanced techniques in ship corrosion analysis: integrating active contour algorithms for image segmentation, Journal of Advanced Research Design 128(1) (2025). 79-99. https://doi.org/10.37934/ard.128.1.7999

[9] T Hasan, et al., S Jamaludin, W B W Nik, Details Design Strategy Analysis of A Hybrid Energy System Boat in Efficient Way, Jurnal Kejuruteraan 37(2) (2025). 555-561. https://doi.org/10.17576/jkukm-2025-37(2)-01

[10] S Jamaludin, N Zainal, W M D W Zaki, Comparison of Iris Recognition Between Active Contour and Hough Transform, Journal of Telecommunication, Electronic and Computer Engineering 8(4) (2016). 53-58

[11] S Ayvaz, K Alpay, Predictive Maintenance System for Production Lines in Manufacturing: A Machine Learning Approach Using Iot Data in Real-Time, Expert Systems with Applications 173 (2021). 114598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114598

[12] M Meherullah et al., Accurate Corrosion Detection and Segmentation on Ship Hull with Pixel Property Method, Journal of Advanced Research Design 129(1) (2025). 148-163. https://doi.org/10.37934/ard.129.1.148163

[13] T M Johansson et al., A Pastra, M Q Mejia, Seaworthiness and Protecting the Ocean: Maritime Remote Inspection Technologies, The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 39(3) (2024). 551-560. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718085-bja10177

[14] S Jamaludin et al., M M H Imran, Practical Application of Artificial Intelligence in Steel Corrosion Analysis, Corrosion Management 181 (2024). 38-41

[15] S Jamaludin, M M H Imran, Artificial Intelligence for Corrosion Detection on Marine Structures, Journal of Ocean Technology 19(2) (2024). 19-24

[16] N I M Jalal et al., A F M Ayob, S Jamaludin, N A A Hussain, Evaluation of Neuroevolutionary Approach to Navigate Autonomous Surface Vehicles in Restricted Waters, Defence S and T Technical Bulletin 16(1) (2023). 24-36

[17] M Shahrami, M Khorasanchi, Development of a Climbing Robot for Ship Hull Inspection, Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences 10(1) (2023). 1-11.[18] S.I. Wahidi, S. Oterkus, E. Oterkus, Robotic Welding Techniques in Marine Structures and Production Processes: A Systematic Literature Review, Marine Structures 95 (2024). 103608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marstruc.2024.103608

[19] IACS, Amendments to the 2011 ESP code, Accessed on 1 May 2025. https://iacs.org.uk/news/iacs-participation-at-sdc-10

[20] A Ortiz, Vision-Based Corrosion Detection Assisted by A Micro-Aerial Vehicle in A Vessel Inspection Application, Sensors 16(12) (2016). 2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/s16122118

[21] Remotion, A splash zone specialist, Accessed on 1 May 2025. https://remotion.no/our-systems/