‘Amber Sykes¹, Danny Burkle², Robert Jacklin1,2 Joshua Owen¹, R Woollam¹, R Barker¹

¹School of Mechanical Engineering, University of Leeds, UK | ²LBBC Baskerville, UK

Amber Sykes is currently a PhD student at the University of Leeds, within the Institute of Functional Surfaces, where she is researching iron carbonate corrosion product formation in geothermal environments. Prior to her PhD research, Amber gained a Master of Engineering (MEng) degree in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Bath. During 2024 she received an EFC – European Federation of Corrosion Award for Best Oral Presentation by an Early Career Author.

Amber Sykes is currently a PhD student at the University of Leeds, within the Institute of Functional Surfaces, where she is researching iron carbonate corrosion product formation in geothermal environments. Prior to her PhD research, Amber gained a Master of Engineering (MEng) degree in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Bath. During 2024 she received an EFC – European Federation of Corrosion Award for Best Oral Presentation by an Early Career Author.

]

1. Introduction: Why Collaboration Matters

This article highlights a collaborative approach in developing a test method to obtain high-quality, reproducible electrochemical data within an autoclave operating at elevated pressure and temperature.

The evaluation and understanding of material corrosivity in high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) environments is critical to ensuring asset integrity in industries such as Oil and Gas, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and Geothermal Energy to name a few. Carbon steel processing infrastructure in these systems is frequently exposed to carbon dioxide (CO2)-containing fluids, accelerating corrosion and threatening long-term integrity.

Under specific CO2 – containing conditions—particularly elevated temperature, pressure, and chemical saturation—the corrosion product iron carbonate (FeCO3) can precipitate onto the internal surfaces of carbon steel pipes. This layer can slow degradation by blocking active corrosion sites and impeding the diffusion of electrochemically active ions [1]. Understanding the formation, structure, and protective mechanisms of FeCO3 layers is therefore vital for accurate corrosion modelling and prediction, and hence asset integrity management.

Autoclave technology can facilitate experimental corrosion testing in HPHT environments, in which protective FeCO3 layers tend to form. In-situ electrochemical monitoring techniques, such as Linear Polarisation Resistance (LPR) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), can provide real-time insight into the rate of FeCO3 layer formation, and the evolving mechanisms of corrosion protection offered by the layer. However, the application of these techniques in HPHT conditions remains exceptionally challenging. Issues such as reference electrode instability, electrical interference, and difficulty maintaining test equilibrium often lead to poor data reproducibility and limit the utility of these techniques for model development and material evaluation.

To address this gap, a collaborative project between LBBC Baskerville and the University of Leeds has advanced the reliability and precision of electrochemical testing in autoclaves. By combining industrial design expertise with academic electrochemical research, the team has developed a refined methodology capable of delivering high-quality, reproducible electrochemical data under extreme conditions.

This article presents two core outcomes of that collaboration:

1.How a refined testing methodology enables reproducible monitoring of corrosion product formation in autoclave conditions.

2.How this data supports advanced EIS modelling to quantify the layer’s physical properties in an autoclave.

Together, these insights offer a practical foundation for enhancing corrosion prediction in real-world HPHT systems.

2. Experimental Set-Up: Refining the Approach

The collaborative work began by identifying recurring limitations in electrochemical autoclave testing. Robert Jacklin’s PhD research project at University of Leeds played a key role in diagnosing failure points, including pressure instability, signal drift, and inconsistent electrode positioning [2].

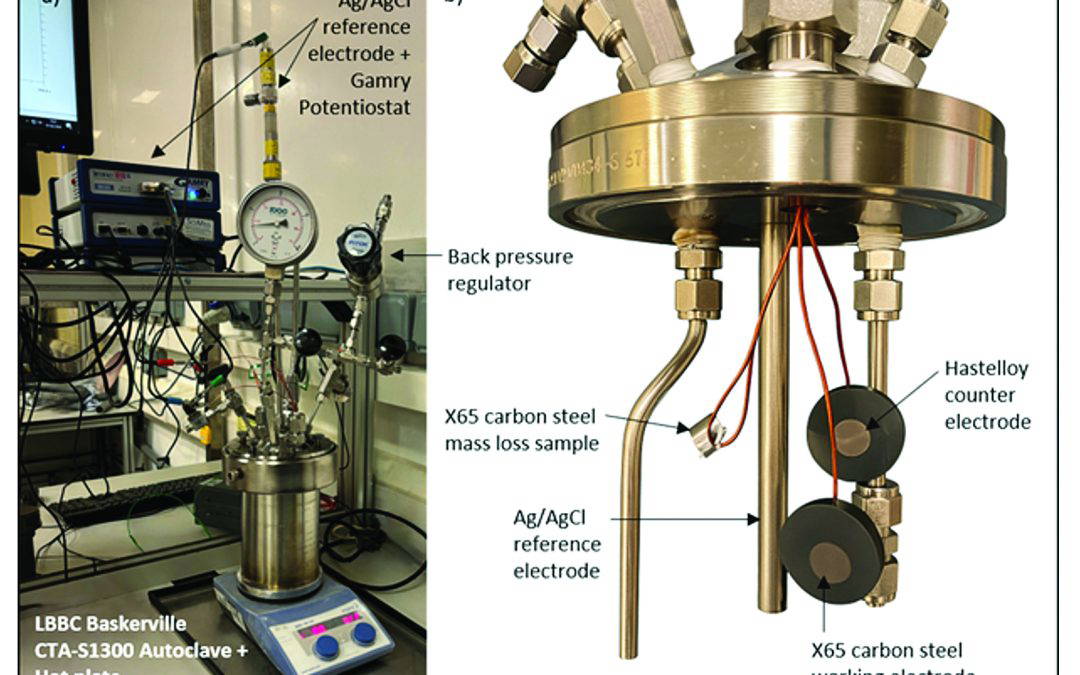

The team developed a refined procedure using the LBBC Baskerville CTA-S1300 autoclave, incorporating:

•Improved sealing methods and sample insulation to prevent electrical interference,

•A low-pressure CO2 sparging method to pre-saturate the brine prior to solution transfer,

•Careful arrangement of working, counter, and reference electrodes to avoid electrical interference,

•Use of a back pressure regulator (BPR) to maintain consistent test pressure during heating.

Electrode Preparation and Assembly

A three-electrode set up was used to take in-situ electrochemical measurements, including an X65 carbon steel working electrode, a Hastelloy C-276 counter electrode and an externally pressure balanced silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) reference electrode. The working and counter electrodes were prepared by wet grinding all surfaces to P600 grit and sealing the back and sides with high-pressure thermosetting resin. An additional X65 carbon steel coupon was prepared for each test to assess mass loss. The arrangement of the electrochemical samples and mass loss coupon in the autoclave is shown in Figure 1.

Brine Preparation and Autoclave Testing Procedure

A 3 wt.% sodium-chloride (NaCl) brine was prepared by dissolving >99 % purity NaCl in deionised water, followed by stirring and continuous CO2 sparging for a minimum of 12 hours to ensure oxygen removal and full saturation. The 1.3L LBBC Baskerville autoclave was also flushed through with CO2 for a minimum of 30 minutes before the brine solution was transferred into the autoclave by CO2 gas displacement.

The autoclave was pressurised to the desired operating pressure (5, 10 or 15 bar) using a high-pressure CO2 line at room temperature, followed by heating to 80 °C using a hot plate and temperature probe. A BPR maintained the test pressure during the heating phase. Upon reaching the target temperature, the outlet valve to the BPR was closed and the pressure in the autoclave was allowed to evolve naturally throughout the test. The working, counter and reference electrodes were connected to a Gamry Potentiostat to take electrochemical measurements. The autoclave vessel was grounded through a metal hot plate [2]. An image of the autoclave set up is shown in Figure 1.

Electrochemical testing followed a repeatable schedule: Open Circuit Potential (OCP), five cycles of LPR, and EIS scans. This setup significantly improved baseline stability and reduced variability across runs. These methods were carefully documented and refined through repeated testing, highlighting how hardware design, procedural control, and pressure regulation directly influence

data quality.

This approach was initially used to refine the procedure and ensure high-quality, reproducible measurements at 5 bar, before being applied in tests at 10 and 15 bar to evaluate reproducibility and environmental sensitivity.

3. Reproducibly Tracking FeCO2 Layer Formation in Autoclaves

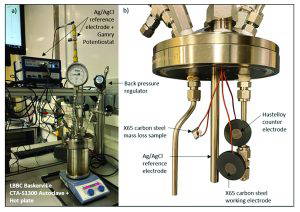

The LPR results in Figure 2 were obtained using the refined autoclave testing set up and show how the average inverse polarisation resistance (Rp-1) varied throughout the 120-hours corrosion tests at 5, 10 and 15 bar. Rp-1 is directly proportional to the corrosion rate of the underlying carbon steel surface. The error bars represent the range in Rp-1 values across four repeats at 5 bar and two repeats at 10 and 15 bar.

The evolution of a protective FeCO3 layer was initially investigated at 80 °C and 5 bar.

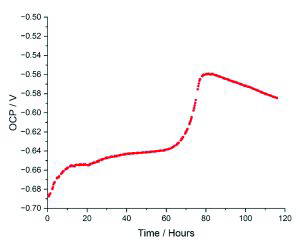

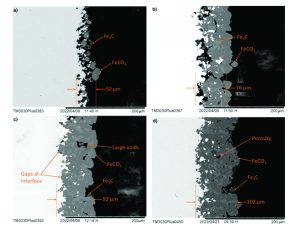

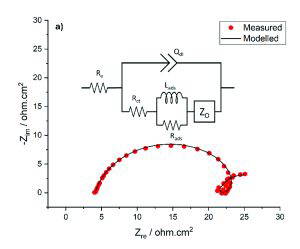

At these conditions, a rapid decrease in corrosion rate occurred after the first 40 hours of exposure, aligning with the onset of FeCO3 precipitation. The EIS Nyquist plots also showed a change in shape from two distinct semi-circles to the formation of a low-frequency linear tail, shown in Figure 5, indicating the transition from active corrosion to a diffusion-limited processes. At this point, the mechanism of protection offered by the FeCO3 layer transitioned from predominantly surface blocking to effectively restricting the diffusion of ions [1]. This occurred alongside the ‘pseudo-passivation’ phenomenon, between 70 and 80 hours, marked by a sudden anodic shift in OCP, shown in Figure 3, and a plateau in polarisation resistance [4]. The cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images in Figure 4 confirm the evolution of a low-porosity FeCO3 layer, consistent with the formation of an effective diffusion barrier, supporting the electrochemical interpretations. These findings validated that the new autoclave methodology could reproducibly capture the entire corrosion-product evolution timeline, from initial exposure through to protective film formation.

The LPR results in Figure 2 also show that the refined autoclave testing methodology could capture repeatable electrochemical measurements in more demanding environments, and with accelerated corrosion kinetics. Increasing the operating pressure from 5 to 15 bar resulted in higher initial corrosion rates and a faster rate of formation of a protective FeCO3 layer [3]. These tests demonstrate the sensitivity of FeCO3 formation and corrosion characteristics to environmental changes and highlights the importance of experimental testing over a wide range of operating conditions.

4. Quantifying Layer Properties Using High-Precision EIS Modelling

The LPR responses in Figure 2 show that corrosion product formation significantly alters the corrosion rate of the underlying carbon steel and must be considered for the accurate prediction of corrosion rates in HPHT environments. However, the current incorporation of FeCO3 into CO2 corrosion models relies on numerous theoretical assumptions regarding the physical properties of the layer, and how these properties contribute towards the mechanisms of corrosion protection [5]. To quantify the protectiveness of corrosion products layers throughout their development, and extract physical properties of FeCO3, equivalent electrical circuit models can be fit to the experimental EIS data.

High-precision EIS data is required to obtain useful and reliable information from equivalent circuit models. To assess the quality of the experimental EIS data, Kramers-Kronig analysis is used. The Kramers-Kronig transformation assesses the validity of the EIS response by testing for linearity, causality and stability [6]. This assessment is particularly important for the low frequency EIS data, used to characterise diffusion behaviour. The time scales required for low frequency measurements are increased, such that the stability condition may not be achieved. Once the EIS data has been validated, the quality of fit between the modelled and measured EIS data is calculated using chi-squared analysis normalised by the degrees of freedom (x2/v). The circuit models illustrated in Figure 5 both achieve an excellent quality of fit to the experimental EIS data, achieving x2/v values of less than 0.0002.

The quality of the electrochemical data in this study was sufficient to extract the full low-frequency EIS response, enabling the quantification of diffusion characteristics through the FeCO3 layer. This represents a significant advancement, as such measurements have rarely been achieved under comparable high-pressure, high-temperature conditions. The circuit models illustrated in Figure 5 were used to quantify the extent of surface coverage from FeCO3, and the diffusion coefficients of ions through the layer. This allows the respective contributions of surface blocking and diffusion restriction towards the overall reduction in corrosion rate to be identified, information that is critical to the advancement of corrosion prediction models.

The physical porosity of the FeCO3 layer was also estimated from in-situ EIS measurements, showing promising agreement with results from literature [7]. Validating the use of electrochemical techniques to evaluate the porosity of corrosion product layers in-situ would be a landmark finding for this research area.

In this study, the development of a robust autoclave testing methodology enabled the collection of high-precision and meaningful EIS data in HPHT environments. Equivalent electrical circuit models could then be utilized to extract physical properties of the layer, in-situ, throughout the layer’s development – information which no other technique can provide.

Standardisation of electrochemical set-ups and autoclave testing procedures will continue to improve EIS data quality and facilitate innovative EIS studies that can further the development of corrosion prediction models and advance the knowledge of the wider corrosion industry.

5. Conclusion: A Path Forward Through Partnership

This collaboration between LBBC Baskerville and the University of Leeds has delivered two critical advances in autoclave corrosion testing:

• A validated methodology for reproducibly tracking FeCO3 layer formation under HPHT conditions using LPR, OCP, and EIS.

• The demonstration that precision EIS can be used to quantify key physical properties of corrosion product layers — such as surface coverage and diffusion characteristics.

These outcomes not only advance the science of corrosion but also provide practical tools and benchmarks for researchers and industry alike. Achieving reproducibility in HPHT electrochemical testing has long been a challenge; this work proves it is possible with the right approach. The success of this collaboration also emphasises a pressing need in corrosion testing to the wider community: standardised methodologies for electrochemical testing in autoclaves.

Without clear standards, comparing data across institutions becomes difficult, and model calibration remains speculative. By publishing detailed methods and validating their approach, this project offers a foundation on which others can build.

The methods and findings shared here are intended to empower others facing similar challenges in autoclave corrosion testing. As CCS, hydrogen, and geothermal technologies continue to expand, the need for reliable, high-precision corrosion data will only grow. This study provides a blueprint for how that data can be generated and used.

Next Steps: The team welcomes further collaboration to extend this methodology to multi-impurity systems and operational-scale environments. For more information or to explore partnership opportunities, contact Dr Danny Burkle (LBBC) and Professor Richard Barker (University of Leeds).

6. References

[1] R De Motte et al., E Basilico, R Mingant, J Kittel, F Ropital, P Combrade, S Necib, V Deydier, D Crusset, S Marcelin, “A Study by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Surface Analysis of Corrosion Product Layers Formed During CO2 Corrosion of Low Alloy Steel”. Corrosion Science 172, (2020): p. 108666.

[2] R Jacklin, Characterising Protective Corrosion Product Development in Demanding CO2 Environments. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, University of Leeds, 2023.

[3] A Sykes et al., R Jacklin, D Burkle, R C Woollam, J Owen, R Barker, “The Effect of CO2 Partial Pressure on the Formation and Protective Characteristics of Iron Carbonate Corrosion Products”. AMPP Annual Conference + Expo, paper no. AMPP-2024-20666 (New Orleans, Louisiana, USA: Association for Materials Protection and Performance, 2024).

[4] W Li et al., B Brown, D Young, S Nešić, “Investigation of Pseudo-Passivation of Mild Steel in CO2 Corrosion”. Corrosion 70, (2014): p.

294-302.

[5] M Nordsveen et al., S Nešić, R Nyborg, A Stangeland, “A Mechanistic Model for Carbon Dioxide Corrosion of Mild Steel in the Presence of Protective Iron Carbonate Films-Part 1: Theory and Verification”. Corrosion 59, 5 (2003): p. 443-456.

[6] A Lazanas, M Prodromidis, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy – A Tutorial. ACS Measurement Science Au. 2023, 3.

[7] R Barker et al., D Burkle, T Charpentier, H Thompson, A Neville, A review of iron carbonate (FeCO3) formation in the oil and gas industry, Corrosion Science, Volume 142, 2018.