MEET THE AUTHORS

Dr Yifeng Zhang is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Non-Destructive Evaluation (NDE) Group at Imperial College London. His work focuses on ultrasonic Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) and inspection technologies that enhance structural integrity and operational efficiency across the energy and petrochemical sectors.

Dr Frederic Cegla is a Reader/Associate Professor in the non-destructive evaluation (NDE) Group at Imperial College London. His research focuses on developing and applying advanced technologies for non-destructive evaluation NDE, SHM, and process monitoring — linking cutting-edge sensing and wave physics with practical solutions for industry.

Introduction: The Challenge of Corrosion Surveillance

Corrosion remains one of the most persistent challenges in managing industrial assets such as power plants, processing facilities, pipelines, and ships. Unlike sudden failures, it develops gradually, often across vast areas and over decades of service.

The result is a degradation process that is both spatially and temporally diverse. Non-destructive evaluation (NDE) techniques such as ultrasonic testing and thickness gauging are widely used to provide critical information that underpins the safety, reliability, and availability of various assets. In practice, it is rarely feasible to perform complete (100%) inspection coverage of large downstream or marine facilities. Instead, inspection areas are typically prioritised using risk-based assessment (RBA) programmes, which focus resources on regions with the highest likelihood or consequence of corrosion Because of these practical constraints, current ultrasonic methods have evolved along two main directions.

Figure 1: Ultrasonic Thickness Measurement Techniques, Trade-Offs Between Spatial Coverage and Temporal Resolution.

Scheduled one-off inspections — often combined with visual assessments and performed using scanning systems — can cover large areas but occur infrequently due to the need for plant shutdowns or limited access [1–2]. In contrast, permanently installed automated monitoring sensors offer improved measurement repeatability and high temporal resolution but are typically deployed only at a few selected locations [3–4] owing to cost and installation complexity.

Towards Hybrid Inspection and Monitoring

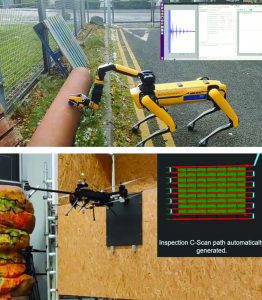

Recent advances in robotics and sensor technologies are creating powerful synergies that blur the line between traditional one-off inspection and continuous monitoring. It is envisaged that autonomous robotic platforms will in future manipulate ultrasonic probes across complex geometries, while monitoring sensors will be deployed in hard-to-reach areas that once required significant manual effort.

Prototypes of resident inspection robots — designed to remain on the asset and operate semi-independently — are moving from research labs towards field demonstrations [5-6].

Figure 2: Integration of EMAT With Robotic Platforms (Image Courtesy of The Offshore Robotics for The Certification of Assets (ORCA) Hub, From Research That Led To The Formation of Sonobotics Ltd).

These developments point towards a hybrid surveillance model that combines the strengths of both worlds as part of the agreed inspection programme. For example, resident robots could perform encoded ultrasonic scans across a structure, leaving behind monitoring sensors in critical regions for long-term trending. There, instead of choosing between wide but infrequent inspections and highly localised monitoring, a mixed approach could provide a more complete picture of corrosion progression in both time and space. The opportunities are clear, but so are the challenges. How many robots or sensors are needed to ensure sufficient reliability and compliance with the agreed overall inspection programme? How does the hybrid scheme align with existing approaches? What are the cost implications and likely return on investment? These questions must be addressed before hybrid inspection-monitoring schemes can achieve widespread adoption.

While current best practices for NDT in the energy sector follow established standards such as API 581 and guidance provided

by organisations such as ESR-HOIS, a forward-looking study funded by the UK Research Centre in NDE (RCNDE) explored new methodologies to systematically evaluate and optimise hybrid inspection–monitoring strategies. [7–8]. This article highlights the main findings of the study, introducing a generic framework applicable across diverse industries and corrosion scenarios.

A Framework for Evaluating Hybrid Inspection–Monitoring Schemes

The proposed framework comprises four essential steps, each of which plays a role in simulating how corrosion evolves, how it is measured, and how the acquired data are interpreted.

1.Corrosion Modelling: Capturing the Degradation Process

The framework begins by establishing a model that accurately captures corrosion damage progression. Corrosion manifests differently across industries—from uniform wall thinning in pipelines to localised pitting in offshore structures and complex mixed morphologies in chemical processing facilities. It is recognised that no single model would suffice for all applications, and different scenarios demand models of varying complexity and fidelity.

While corrosion mechanisms vary widely, ultrasonic NDE measurements share a common dependency: the corroded surface profile. Since wave reflection from the corroding surface dictates the characteristics of measured ultrasonic signals, a suitable corrosion model must capture both the relevant surface morphology and its temporal evolution.

This approach decouples electrochemical complexities from NDE simulation requirements, enabling the corrosion model to be readily updated or substituted for different scenarios.

2. Modelling the NDE Technique

The second stage involves accurately representing the NDE method itself. Like all measurement systems, NDE techniques inherently contain errors and uncertainties. For instance, as part of theHOIS Joint Industry Project [9-10], the measurement error and uncertainties of several manual and automated corrosion mapping methods were evaluated, and the findings were found to vary significantly depending on the choice of equipment.

For normal-incidence ultrasonic thickness measurements, the signal depends on multiple factors: transducer characteristics (e.g. size, shape, operating frequency) and surface conditions (e.g. roughness) [11-12]. Signal processing algorithms further influence measurement outputs, with algorithm selection typically based on the expected defect type. Understanding and quantifying these error sources is crucial, as they propagate through to all subsequent analyses and decision-making processes.

While finite-element simulations can accurately capture wave propagation phenomena, their computational demands make statistical analysis of stochastic corrosion processes challenging. Surrogate models — either physics-based or data-driven—offer a practical alternative by balancing computational efficiency with accuracy. These simplified models enable systematic evaluation of NDE techniques while maintaining sufficient fidelity to represent real-world performance.

In practice, multiple models may be required to represent different equipment types, and these can later be integrated and refined as field experience accumulates. Ultimately, the chosen NDE model must reflect the technique’s inherent limitations and uncertainties as encountered in field applications.

Figure 4: Illustration Of The Ultrasonic Scanning Measurement: Comparison Between The True Underlying Surface And The Thickness Measurement Map Predicted By A Surrogate Model.

3. Simulation of Data Acquisition Processes

The third stage models the data acquisition process, addressing real-world constraints such as operational access, spatial scanning resolution, limited probe availability, and restricted temporal measurement frequency. By focusing on data subsampling in time and space, the framework accounts for the incomplete nature of field measurements caused by sparse grids, irregular intervals, and missed data points. These constraints ensure a realistic representation of field deployment scenarios, enabling accurate assessments under practical conditions.

4.Defining Metrics of Reliability and Risk

Once simulated data are available, the next step is to establish performance assessment criteria. This involves defining a clear corrosion assessment objective, such as detecting defects above

a specified threshold or tracking the location and extent of the minimum remaining thickness. Ideally this data collection should be combined and reported along with prevailing operating parameters / modes e.g. cyclic operation to provide added value.

Quantitative metrics, such as the probability of detection (POD) or receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, are then applied. These metrics are evaluated on an ensemble of representative surfaces using Monte Carlo-style simulations to assess the effectiveness of various NDE data acquisition techniques and procedures. A proof-of-concept demonstration is detailed in Reference [7], where the objective was set to tracking the minimum remaining thickness within a defined tolerance. The study introduces a metric called the unreliability function (URF) to quantify the reliability of inspection and monitoring schemes. Using an ensemble of realisations that mimic field measurement characteristics, the study evaluates the reliability of three strategies: surface scanning, monitoring with permanently installed sensors, and a hybrid approach combining surface scanning with movable monitoring sensors. For the given scenario, the findings reveal that partial surface scanning followed by sensor repositioning/optimisation creates a hybrid strategy that substantially improves performance despite reduced operational demands: fewer sensors per location, limited coverage, and longer inspection cycles.

Conclusion and Outlook

Although manual inspection will continue to play an essential role in ensuring the structural integrity of critical infrastructure, advances in automation and robotics now make it feasible for an increasing proportion of inspection and monitoring activities to be performed automatically. In practice, adopting a hybrid inspection–monitoring strategy provides a promising means of optimising data collection and enhancing overall asset integrity.

The framework presented here outlines a structured approach

for evaluating hybrid inspection-monitoring schemes that

leverage recent advances in robotics, sensing, and modelling.

By clearly defining the interfaces between corrosion modelling, data acquisition, and performance evaluation, it supports the development of more flexible surveillance methods for industrial assets. Successful implementation requires coordinated efforts among corrosion engineers/scientists, NDE engineers, asset owners, and regulators. Key priorities include adapting models to specific industrial settings, validating performance through field studies, and developing accessible tools for practitioners. This progression from theoretical framework to practical implementation will enhance operational safety, asset availability, and economic efficiency.

References

1. J. Turcotte et al., “Comparison corrosion mapping solutions using phased array, conventional UT and 3D scanners,” 19th World Conference on Non-Destructive Testing (WCNDT 2016), 13-17 June 2016 in Munich, Germany. e-Journal of Nondestructive Testing Vol. 21(7). https://www.ndt.net/?id=19236.

2. V. P. Nikhil et al., “Flaw detection and monitoring over corroded surface through ultrasonic c-scan imaging,” Engineering Research Express, vol. 2 no.1, pp. 015010, jan 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/ab618d.

3. F. B. Cegla et al., “High-temperature (>500°c) wall thickness monitoring using dry coupled ultrasonic waveguide transducers,” IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 156–167, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1109/TUFFC.2011.1782.

4. C. H. Zhong et al., “Investigation of Inductively Coupled Ultrasonic Transducer System for NDE”. IEEE Transactions

on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, vol.

60, no. 6, pp. 1115–1125, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1109/TUFFC.2013.2674.

5. V. Ivan et al., “Autonomous non-destructive remote robotic inspection of offshore assets,” In Proc. OTC Offshore Technology Conference, May 2020, pp. D011S006R003. https://doi.

org/10.4043/30754-MS.

6. M. D. Silva et al., “Using External Automated Ultrasonic Inspection (C-Scan) for Mapping Internal Corrosion on Offshore Caissons,” In Proc. Offshore Technology Conference Brasil, 2023, pp. D031S033R001. https://doi.org/10.4043/32907-MS.

7. Y. Zhang and F. Cegla, “Quantitative evaluation of the reliability of hybrid corrosion inspection and monitoring approaches,” NDT & E Int., 2025, pp. 103527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ndteint.2025.103527.

8. Y. Zhang and F. Cegla, “Mon ami – monitoring and inspection strategy assessment investigation tool”. Accessed: July 18, 2025. https://www.pogo.software/monami/index.html.

9. S. F. Burch, “Precision thickness measurements for corrosion monitoring: initial recommendations and trial results”, HOIS, vol. 11, R3, no. 1, 2011.

10. S. Mark, “HOIS recommended practice for statistical analysis of inspection data – issue 1”, HOIS, 2013.

11. R. Howard and F. Cegla, “The effect of pits of different sizes

on ultrasonic shear wave signals,” in Proc. AIP Conference Proceedings, Aug. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5031544.

12. D. Benstock et al., “The influence of surface roughness on ultrasonic thickness measurements”. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 2014, vol. 136, no. 6, pp.3028–3039. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4900565.