The cart is empty!

Atmospheric Corrosion Control for Exposed Bridge Structures – A Case Study of Tamar Bridge, UK

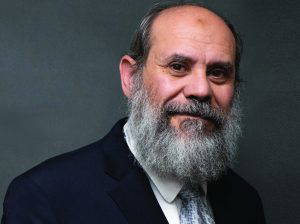

Kevin Harold is a Director at Paintel Ltd. He is a Level 3 ICorr Painting Inspecto

Thomas Harold is employed as the Paintel Contracts Manager and is also a Director of Paintel Ltd. He is IPAF & IRATA qualified and an ICorr Level 2 Painting Inspector and ICATS approved Industrial Painting Supervisor with more than 15 years’ experience of applying protective coatings.

Introduction

This article is about the environmental effects and maintenance painting required for ‘Atmospheric Corrosion Control’ on exposed bridge structures and, in particular, the Tamar Bridge linking Devon and Cornwall on the A38 trunk road.

Spanning the River Tamar by the side of Brunel’s famous Saltash railway bridge, the new Tamar Road bridge provided an important new link by road between the City of Plymouth and the county of Cornwall. It was opened in October 1961; it has a total suspended length of around 335 meters plus two side spans and a water-level clearance of between 32 and 35 meters. All in all, a weighty corrosion problem.

Photo: Overview of the Tamar Bridge With Cheery Picker Painting Maintenance Ongoing.

The structure carries around 50,000 vehicles per day in each direction. and is located in a fairly aggressive marine environment, towering over the river Tamar as it flows further into Cornwall in one direction and towards Devonport Dockyard in the other. The bridge has been in continual service since opening, even when it had two cantilevers added and coated during 1999-2000, under the supervision of Paintel.

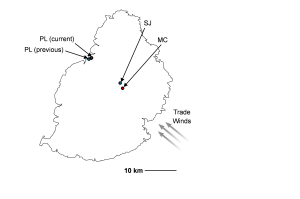

Corrosivity of Bridge Environment

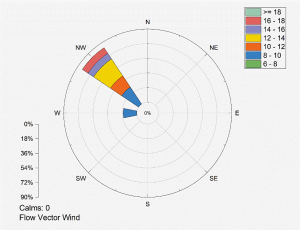

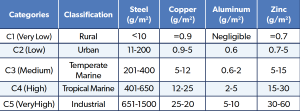

Its corrosivity classification in accordance with ISO 12944 (the accepted standard that sets out rules for the protection of assets from corrosion by use of coating systems and paint, originally released in 1998) probably ranges between a C4 and C5 (high to very high), plus the effects of the driving Southwest rain and winds, keeping it wet/damp for long periods, and also depending on the geography of the structure, causing corrosion deposits to build up.

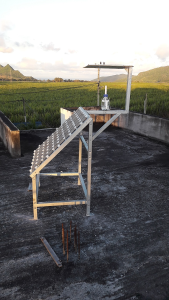

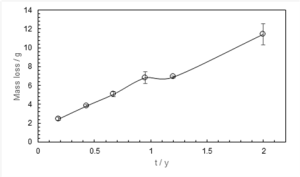

The Tamar Bridge’s unique location over the tidal River Tamar and exposure to marine elements means site-specific monitoring and protection are critical for its structural integrity. Engineers conduct routine inspections normally every four months and use advanced techniques including test gauges to measure the depth of corrosion on main cable ropes, to monitor the progression of corrosion.

Challenges and Costs

The bridge’s annual maintenance cost is approximately £2 million, with significant, multi-million-pound projects funded by tolls to specifically address issues like corrosion and deck resurfacing.

As with many similar suspension type bridges, preparation and re-painting of the Tamar Bridge is not without its challenges. When you drive over any bridge you tend to only notice everything at ground/deck level, occasionally you might glance up to the towers and think my goodness that’s high or how on earth do you access that?

Working on tower tops or beams roadside of course involves significant challenges, as does painting beneath the deck level, and that is the case for all types of bridge structures really.

Photo: Distance Harness Assisted Solvent Wash Under Deck.

The steel arrangement beneath deck levels can appear to be very complex and once again your thoughts turn to how would you go about accessing what you might think is particularly inaccessible. Each area not only comes with access challenges but also must address the type and classification of corrosion at any location and how fast it may be progressing, particularly with structurally important fixings and smaller detail areas where corrosion is simply not acceptable.

Maintenance Painting Process and Access

Of course, it would very helpful if you could scaffold a bridge or structure every time maintenance was required or there was a permanent one in place (designed-in), but this can be expensive and time consuming and a quicker fix is often what’s required, providing of course, the quicker fix is acceptable and safe to all.

Access options at the Tamar Bridge do include scaffolds, but only when other methods are considered too dangerous or the works required will be of long duration. The Tamar Bridge has 4 gantries, two main deck and two cantilever gantries; these give access to many locations, but not directly underneath the deck and some other important areas.

Paintel has a MEWP (Mobile Elevating Working Platform)-trained team as well as a RAT (rope access trained) team using rope access methods for preparing, painting, repairing or cleaning surfaces. All these techniques allow us to paint areas that might appear at first to be inaccessible.

Photo: MEWP (Mobile Elevating Working Platform).

Selective Corrosion Repair Sites

You would have heard people say, “It’s like painting the Forth Bridge; I suppose you start at one end and work towards the other and then start again,” but this couldn’t be further from the truth. Corrosion is very selective, and the geography and geometry of a structure play a huge part in corrosion risk and corrosion rates, as well as the conditions each part is exposed to. Then add in some contamination, and different types appear: general, pitting, crevice and galvanic, to mention a few.

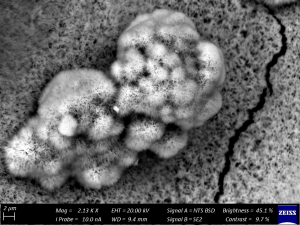

Corrosion first needs a base metal, steel most commonly, an electrolyte, water, or other, and of course oxygen to corrode/ oxidise any steel. Corrosion areas and rates vary considerably across the structure according to geometry and degree of exposure.

Photo: Bridge Hangar Painting.

Geography and Geometry

High sections (pier/tower tops) are prone to additional exposure, high and low temperatures, intense UV light, continuous wetting and drying, and North, South, East or West perspectives. Of which South dries the most, North dries the least, West is wetter, and East will be cooler; all of these conditions affect corrosion rates.

Many of these areas are accessed by ‘rope access’ methods, as many of the team are IRATA (Industrial Rope Access Trade Association) trained, with a level 3 RAT Team Lead.

Photo: Metal Coating Using A Trug.

RAT work necessitates:

- A Head for Heights

- Exposure to extremes of Climate

- High levels of Fitness

The compensation for operatives is some of the best views a person can have.

Deck/Road Level – Traffic Issues

Exposed, but not the same exposure as the tops of the towers. Higher and lower temperatures. Temperatures can be higher at this level due to radiated heat from the road surface, lower windage and other protection from parapets/tower bottoms and cabins/storage areas. UV intensity remains high, and many surfaces remain wet for long periods due to drainage design with water weepage long after rain has stopped. Contaminated surfaces from traffic activity and the effects of north, south, east or west winds, perspectives all contributing additional corrosion effects.

Temperatures can be lower due to more standing water and ice during the winter and additional shading from piers and storage containers. Surfaces are also wetted and dried continuously with the additional consideration of contaminants.

Pollution from passing vehicles, salt from salt spreaders during winter months, and sludges created by dirt and wet from vehicles that do not dry all add to ongoing corrosion rates and challenges.

Below Deck

These areas are often the most prolific in terms of workload. Much more structural steel is being affected by microclimates. Other factors that influence corrosion rates include being closer to the water/river, rain run-off (from the deck), salt contamination from road salting and bird contamination. Little or no direct sunlight and non-drying of surfaces, sludges and slurry build-up accelerate corrosion rates enormously.

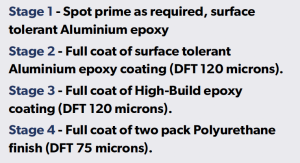

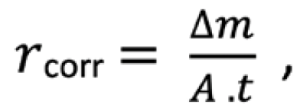

Preparation and Painting Specifications

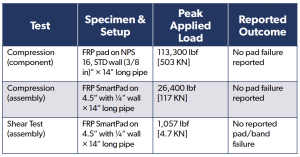

Because of the environmental difficulties associated with blasting, set-up, noise, encapsulation, danger, dust, time factor, clean-up, and spillage, all the preparation prior to painting is done by mechanical preparation standards. This is therefore normally done using small tools like needle guns, grinders, sanders, scrapers, etc., but not before precleaning with degreaser to remove most of the dirt and grease. All surfaces are then prepared to an ISO 8501-1 ‘very thorough’ surface preparation. Once an area of preparation is complete and re-cleaned, it is then inspected for quality control for acceptance. After acceptance, all areas receive a multi-coat paint system of:

The final dry film thickness (DFT) is in excess of 300 microns throughout (higher at spot primed locations).

The paint system being utilised can change depending on prevailing corrosion classification to include additional build with MIO, micaceous iron oxide. The bridge is subjected to a maximum of 6 monthly inspections, sometimes more frequent depending on the site zone, and these inspections flag up the more corroded affected areas, and they become priority work packages. Paint is most usually applied by brush and roller. This avoids problems associated with potential overspray and sheeting issues.

Photo: Incline Cable Painting.

Paint Lifetime Expectancy

In the coating business we often discuss and compare lifetime expectations of different types of preparation and painting techniques. Although many would argue that there is nothing better than blasting prior to painting with all the rules in place, as experienced coating applicators, we have proven ‘year on year’ that if you do thoroughly clean surfaces, prepare to the correct standard and paint to the specification, then this work will also last a very long time, often 10 years plus. Our extensive work on the Tamar Bridge has proved this conclusively.

References

BS EN ISO 12944 (2019) – Multi-part Document – Corrosion protection of steel structures by protective paint systems.

Bridging The Tamar Visitor Centre | Tamar https://www.tamarcrossings.org.uk

‘Daredevil decorators’ protecting Tamar Bridge from corrosion – BBC https://www.bbc.co.uk

Structural health monitoring of the Tamar suspension bridge | Request https://www.researchgate.net

Tamar Bridge | VolkerLaser. https://www.volkerlaser.co.uk