The cart is empty!

A New Approach to Explore Passivation Characteristics of Type 316L Stainless Steel

Yosef Thio Widyawan, Dirk L Engelberg

Metallurgy and Corrosion, Department of Materials, School of Natural Sciences,

The University of Manchester, United Kingdom

(*The work reported here is based on Yosef’s dissertation for the MSc in Corrosion Control Engineering (CCE) at The University of Manchester).

1. Introduction

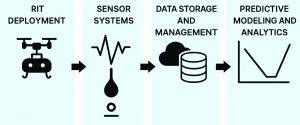

Austenitic stainless steels are commonly used for applications in the energy, medical and chemical process industries due to their enhanced corrosion resistance, ease of availability and beneficial physical properties [1]. However, the material is not immune to corrosion, which is frequently caused by chlorides and other halide ions that may be present in petrochemical refinery systems or marine atmospheres [2]. Such corrosion damage can lead to serious material loss, crevice or localised corrosion or even stress corrosion cracking (SCC). Thus, monitoring, inspecting, predicting and investigating the corrosion behaviour and its patterns are most important to avoid the risk of material failure and to ensure the materials are performing accordingly.

Passivation treatments are viable options to enhance the corrosion resistance of stainless steels, providing an additional layer of protection

via enhancing surface passive film properties. These treatments are either applied via exposure to citric or nitric acids [3,4,5] or via electrochemical treatments [6]. Passivation treatments strengthen the existing passive film of stainless steel surfaces, but there will likely often remain some residual issues at sites of jointing and particularly welding.

A novel method for screening materials for their corrosion resistance is bipolar electrochemistry. The technique has been used for high-throughput corrosion screening and to obtain information about microstructures that might provide enhanced protection against material degradation [7,8].

The idea of this dissertation is to explore bipolar electrochemistry for modifying passive film properties on type 316L stainless steel.

The set-up does not require a direct ohmic contact to the test sample, and the set-up is quite simple and easy to replicate. A bipolar electrode (BPE) is an electrically conductive substance that encourages electrochemical reactions at its extremities (poles) when exposed to an electrical field between two feeder electrodes [9]. Through bipolar electrochemistry [10], the material’s surface properties can be either modified or assessed.

Differing from the conventional three-electrode experimental corrosion test, the bipolar set-up can be used to conduct corrosion assessment across a far wider range of applied potentials and materials. Bipolar electrochemistry has even been used to screen 2707 Hyper-duplex stainless steels for their corrosion resistance [11]. This is possible through scan rate independent, directly acting potential gradients along the BPE. In addition, one of the studies related to the oil and gas industries is the employment of cathodic protection, where stray current can be further studied via bipolar electrochemistry utilisation or the formation of inhibitor films under anodic or cathodic polarisation control. These test set-ups are currently being further developed for corrosion screening.

2. Methodology

Material and Sample Preparation

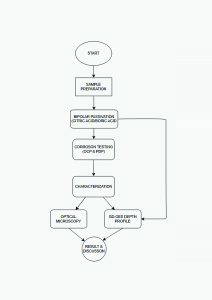

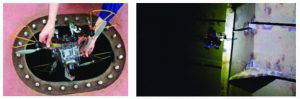

Type 316L sheet samples with dimensions of 10 mm x 25 mm were mechanically prepared with SiC paper from 400 up to 2500 grit, then polished with diamond paste to a ¼ micrometre finish. The final mirror-finished surface is required for passivation and corrosion test experiments—the desired quality of sample finish is also needed for elemental depth profile analysis with Glow Discharge Optical Emission Spectroscopy (GDOES). Figure 1 gives a flow chart of the research methodology and analysis steps applied. The prepared samples were first passivated using a novel bipolar electrochemistry approach, followed by assessment of the passivated surfaces in HCl solutions using standard 3-electrode electrochemistry. The sample surfaces were then analysed after corrosion testing using optical microscopy. One additional sample was also prepared under bipolar passivation treatment (in citric acid and boric acid) in order to observe the GD-OES depth profiling effect of bipolar passivation treatment.

Bipolar Electrochemistry Passivation Treatment

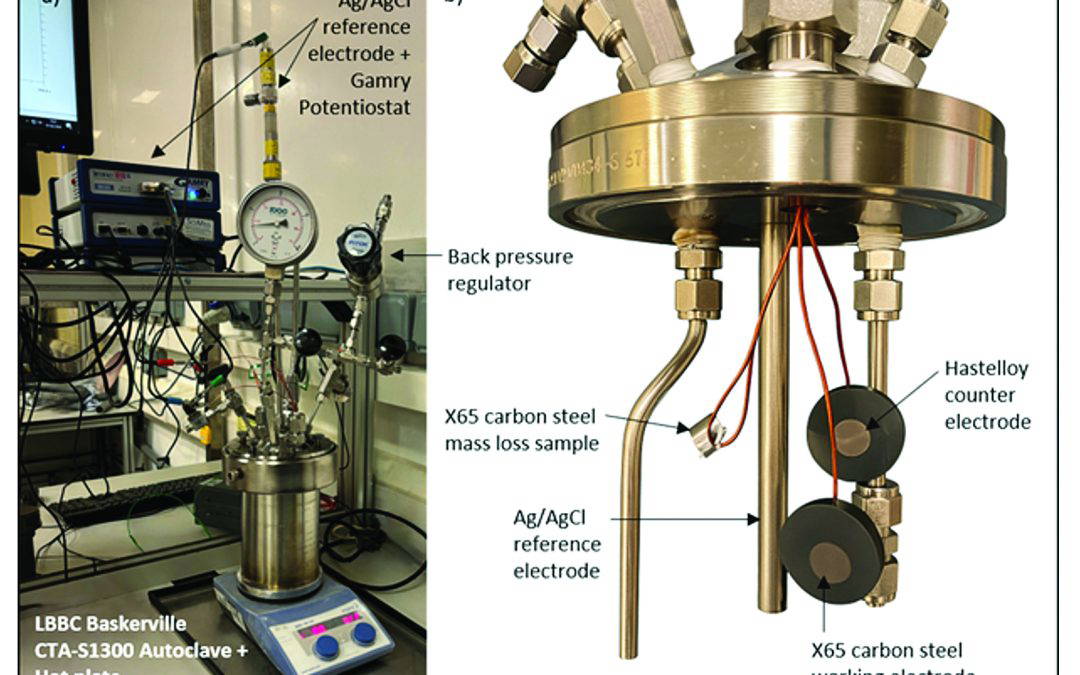

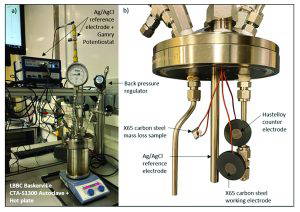

The passivation treatment utilised citric acid (C6H8O7), and boric acid (H3BO3) as passivating agents in order to facilitate the formation of a gradient passivation layer along the BPE surface. Employing bipolar electrochemistry to induce passivation at the anodic side, with the cathodic side expected to weaken the passive film. The expected outcome here was to generate one sample surface containing the full spectrum, starting with a strong passive film at the anodic side, to surfaces experiencing OCP conditions close to the central region, to a cathodically cleaned surface at the cathodic end of the BPE. Figure 2 below shows the bipolar test set-up, with the sample exposed to the electric field between both feeder electrodes, but without any electrical connection to an outside power source. Here it was expected that the negative pole of the feeder electrode would induce a positive reaction at the one end of the BPE surface, with the positive feeder inducing a negative pole at the BPE. The set-up was similar to experiments to test stray current corrosion of different metals related to cathodic protection as well as buried power line corrosion [12,13].

The effect of cathodic polarisation on passive film stability has been demonstrated previously under different applied potentials on super duplex stainless steel [14].

The bipolar parameters used for the passivation treatment were 8V with 10-minute or 30-minute polarisation in 10% (wt.) citric acid or 1 M boric acid. A Keysight power source was was used for applying the voltage. For surface film characterisation GDOES depth profile measurements were carried out, and each experiment was conducted 3x for each parameter variable.

Directly after the bipolar passivation treatment, standard 3 electrode potentio-dynamic corrosion tests were carried out to assess the effect of the surface passivation treatment. An 0.01 M, 0.1 M and 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution was used with Ag/AgCl/saturated KCl reference electrode.

Open circuit potential (OCP) measurements were recorded for 180 minutes, to see whether changes occurred at the surface that might be reflected in a shift of the OCP. The assessed samples were then observed under an optical microscope to analyse the impact of the corrosion testing on the treated sample surfaces.

Glow Discharge Optical Emission Spectroscopy (GDOES)

The depth profiles of the sample surface were measured using a GD-OES instrument. The power output used was 30 W and 650 Pa. with the sample very flat and the backside of the sample parallel to the front side to enable the vacuum to work properly. GD-OES analysis was carried out at both ends and the centre of the sample after passivation.

3. Results and Discussion

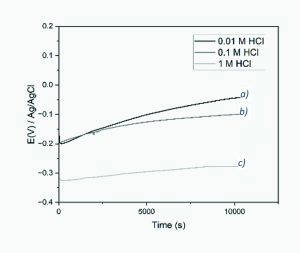

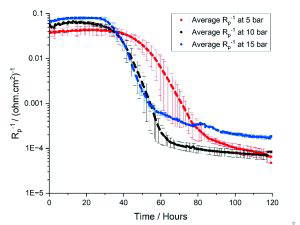

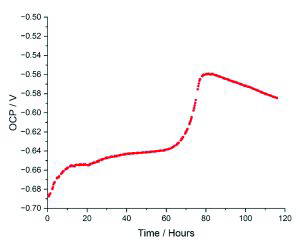

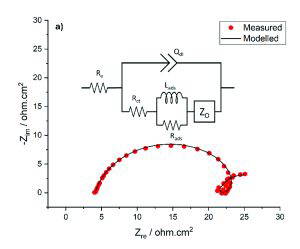

Figure 3 below shows the OCP versus time for the untreated type 316L surface. The test in 0.01 M HCl shows a steady increase of OCP from -0.2 V at the start to about -0.05 V after 3 hours, with the 0.1 M HCl giving a final rest potential close to -0.1 V, and the 1 M HCl sample somehow stabilising at -0.3 V. These long OCP measurements were employed to understand whether the bipolar passivation treatment caused changes in the OCP response.

Figure 4 further summarises the OCP response of the citric and boric acid treated BPE surfaces, with the same trend apparent for all samples. The OCP test for citric acid passivation exposed to 0.1 M HCl started at -0.2 V and stabilised at -0.13 V, with the only marked difference observed for the boric acid treated surface giving an initial potential of +0.3 V. Although the final potential was slightly less positive than the 0.1 M HCl test of the untreated type 316L surface, it still showed the material’s resistance was in a similar OCP range.

Furthermore, the OCP test for both passivation treated surfaces exposed to 1 M HCl started at -0.35 V and gradually rose to about -0.28 V, then remained steady until the end of the test at 3 hours. Both passivation treatments showed a distinct OCP stabilisation hump after 1 hour of exposure. This shows the system reaches a stable state, but at a far more negative potential compared to the lower HCl concentration.

The bipolar passivation treatment was expected to enhance the passive layer at the anodic side of the bipolar electrode, leading to a more corrosion resistant surface, compared to the cathodic side. However, since the full sample was immersed in the passivating solutions, even the central part would be expected to be more resistant than the cathodic, with the later cathodic BPE side is expected to have a far weaker passive film [14].

Although all the results show a similar behaviour, when the corrosion test was deployed in 1 M HCl, the treated sample obtained a constant OCP far earlier than the reference sample test; this could be due to the effect of passivation treatment, which enabled the samples to obtain their equilibrium earlier than the reference sample without passivation treatment [15].

Comparing the results of the samples that have been treated with bipolar passivation in 10% citric acid and 1 M boric acid in Figure 4, the OCP data showed no particular difference between them. The application of bipolar electrochemistry on the citric acid and boric acid passivation showed a similar behaviour when immersed in the 0.1 M HCl and 1 M HCl.

Figure 5 above summarises the optical microscopy observations of both sample surfaces that underwent bipolar electrochemistry passivation treatment in 10% citric acid and 1 M boric acid, which were corrosion in both 0.1M and 1M HCl solutions. The optical assessment showed no significant corrosion attack variation between the anodic and the cathodic pole of the BPE sample. The difference in 0.1M to 1M HCl exposure clearly showed more general surface roughening, with the appearance changing into a “wrinkle-like” roughened contour after 1M HCl exposure. Type 316L is known to readily corrode in 1M HCl.

The idea of this OCP exposure test in HCl was to understand whether differences exist between the anodically and cathodically treated sides after the bipolar passivation treatment. No visual differences were actually observed along the sample surface after both 0.1M and

1M HCl exposure.

Characterisation

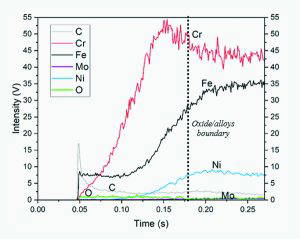

GD-OES application for surface chemical analysis is described in more detail in Ref. [16,17]. The plasma generated during the measurement will create a circular crater of 4 mm in diameter, as shown in Figure 6 below. The scan rate was 1 m/s to obtain the depth profiles with a sputter duration of 75 seconds, with measurements taken at different locations. The collision between the argon ions and the sputtered material excites atoms and releases the photon energy as a characteristic light spectrum. The data obtained from the measurements shows the emission intensity versus time (s). GD-OES is frequently used for the depth profiling of thin surface films and layers, such as passive surface films, galvanised materials, or PVD/CVD coatings [18].

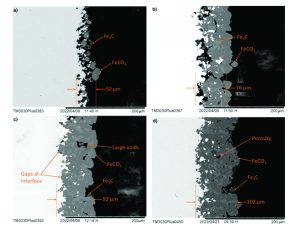

All data obtained showed carbon contamination at the surface, which is expected with sample storage under standard ambient conditions in the laboratory. Figure 7 above shows the resulting GD-OES depth profile of the reference Type 316L sample, with carbonaceous surface contamination, followed by enriched chromium, with the iron (Fe) and nickel (Ni) then indicating the bulk composition. The oxygen signal was found slightly raised in the surface region, with the horizontal line then indicating a drop in this signal, indicative of the interface between surface oxide and the bulk.

Finally, Figure 8 below compares the GD-OES depth profiles of the specimens treated in 10% citric acid and 1 M boric acid. The application of the bipolar passivation treatment seemed to influence to some degree the formation of the passive film of the Type 316L sample. The passive film formation of the sample under passivation treatment in 10% citric acid showed some minor change in chromium signal between the middle region and both anodic and cathodic regions. The middle region shows the presence of iron on the outer surface, while chromium dominates both the anodic and cathodic poles [19].

Observation of the cathode side of the passivated sample (both in citric and boric acid – Figure 8) showed a higher intensity level of chromium at the very beginning of the time axis. This may indicate that the chromium exists at the very outer layer of the treated sample’s cathode side; therefore, the treated sample had higher chromium content on the passive layer than the untreated sample. This behaviour might be influenced by the application of bipolar passivation treatment on the sample, which strengthens the formation of a passive layer on the sample’s cathode side.

The chromium intensity of the sample treated in 10% citric acid fell before it reached the bulk interface. On the other hand, the sample treated in 1 M boric acid underwent a falling of chromium intensity before it went constant at the bulk layer. According to Ref. [36], the peak of the elements chromium and iron showed that the elements were the major cationic alloys in the redox reaction. Thus, it can be assumed that applying 1 M boric acid was a more susceptible, favourable environment for the passivation of stainless steel 316L compared to the treated sample in 10% citric acid.

Conclusion

The overall bipolar passivation treatment did not show the expected behavior regarding the formation of a gradient passive film, although some interesting response was observed conducting OCP measurements in 1 M HCl solution.

It seems though that the application of bipolar passivation treatments influences somehow local passive layer compositions. From GD-OES characterisation of the sample passivated in 10% citric acid, the anodic and cathodic regions seemed Cr enriched in the oxide layers, while the middle part of the surface remained covered with iron oxide. On the other hand, on the sample exposed to 1 M boric acid, the anodic and centre part of the sample have iron oxide at the outer film surface, while the cathodic region was enriched with chromium. More work is certainly needed to further investigate the successful application of bipolar passivating treatments.

References

[1] P Kangas and G C Chai, “Use of Advanced Austenitic and Duplex Stainless Steels for Applications in Oil & Gas and Process Industry,” AMR, vol. 794, pp. 645–669, Sep. 2013, doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.794.645.

[2] A H Al-Moubaraki and I B Obot, “Corrosion Challenges in Petroleum Refinery Operations: Sources, Mechanisms, Mitigation, And Future Outlook,” Journal of Saudi Chemical Society, vol. 25, no. 12, p. 101370, 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jscs.2021.101370.

[3] ASTM A380-99E1 Standard Practice for Cleaning, Descaling, and Passivation of Stainless Steel Parts, Equipment, and Systems, 2017. doi: 10.1520/A0380_A0380M-17.

[4] ASTM A967-05E2 Standard Specification for Chemical Passivation Treatments for Stainless Steel Parts, 2013. doi: 10.1520/A0967-05E02.

[5] BS EN 2516:2023 Aerospace Series – Passivation of Corrosion Resisting Steels and Decontamination of Nickel or Cobalt Base Alloys, BS EN 2516:2023, Feb. 06, 2024. doi: 978 0 539 30425 1.

[6] ASTM B912-02(2018) Standard Specification for Passivation of Stainless Steels Using Electropolishing, 2018. doi: 10.1520/B0912-02R18.

[7] Y Zhou, J Qi, and D L Engelberg, “A Novel High Throughput Electrochemistry Corrosion Test Method: Bipolar Electrochemistry,” 2023.

[8] Y Zhou, J Qi, and D L Engelberg, “On The Application of Bipolar Electrochemistry For Simulating Galvanic Corrosion Behaviour of Dissimilar Stainless Steels,” Electrochemistry Communications, vol. 126, p. 107023, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2021.107023.

[9] S E Fosdick et al., “Bipolar Electrochemistry,” Angew Chem Int Ed, vol. 52, no. 40, pp. 10438–10456, Sep. 2013, doi: 10.1002/anie.201300947.

[10] R M Crooks, “Principles of Bipolar Electrochemistry,” ChemElectroChem, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 357–359, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.1002/celc.201500549.

[11] Y Zhou et al., “A Rapid Corrosion Screening Technique for Grade 2707 Hyper Duplex Stainless Steel At Ambient Temperature,” Materials and Corrosion, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 227–234, 2023, doi: 10.1002/maco.202313943.

[12] T J Lennox and M H Peterson, “Stray Current Corrosion of Steel, ”Naval Engineers Journal, vol. 88, no. 1, pp. 45–53, 1976, doi: 10.1111/j.1559-3584.1976.tb03795.x.

[13] J M K Nairn et al., P Wade, and S Thomas, “Cell-Within-Cell Study of Stray Current Copper Corrosion: Impact of Soil Conductivity and Source Distance,” Corrosion Engineering Science and Technology, The International Journal of Corrosion Processes and Corrosion Control, 2025, doi: 10.1177/1478422×241311671.

[14] C Ornek et al., “Understanding Passive Film Degradation and Its Effect On Hydrogen Embrittlement of Super Duplex Stainless Steel – Synchrotron X-Ray And Electrochemical Measurements Combined With Calphad And Ab-Initio Computational Studies,” Applied Surface Science, vol. 628, p. 157364, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.157364.

[15] S Mischler and A I Munoz, “Tribocorrosion,” in Encyclopedia of Interfacial Chemistry, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 504–514. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-409547-2.13424-9.

[16] R Payling and T Nelis, Glow Discharge Optical Emission Spectroscopy: A Practical Guide. Royal Society of Chemistry, 2007. Available:https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7mwoDwAAQBAJ&dq=glow+discharge+optical+emission+spectroscopy+&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s

[17] LECO Corporation, Michigan, USA. GDS Series Glow Discharge Spectometers Product Video, (2023).

[18] T Nelis and R Payling, Surface Analysis Methods in Materials Science. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [Online]. Available: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-662-05227-3_24

[19] M Uemura et al., “Depth Profile Analysis of Thin Passive Films on Stainless Steel By Glow Discharge Optical Emission Spectroscopy,” Corrosion Science, vol. 51, no. 7, pp. 1554–1559, Jul. 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2008.11.017.